Unless you have been hiding under a rock, you’ll know something about hydraulic fracturing, or fracking as it's commonly known. This process involves, "The high-pressure injection of a cocktail of water, sand and a variety of chemicals thousands of feet underground to crack open rock formations and stimulate the release of natural gas." Well that's the Huffington Post definition anyway. Governments and energy companies around the world tell us that shale gas is a panacea for our energy shortages, a boon for national economies, even a life-changing source of revenue for land owners in countries such as the US. With the world's population exploding towards the 10 billion mark by 2050 and energy consumption projected to rise by more than 50% between now and 2040, surely this untapped resource is good news? Or is fracking as sinister as it sounds?

It depends on who you speak to. Fracking has certainly raised environmental and health concerns ranging from water contamination caused by potentially carcinogenic chemical and methane leeks from poorly constructed wells, to the gargantuan levels of water required to stimulate them and the significant amount of toxic wastewater produced in the process. There is profit to be had, but at what cost?

Bouyed by the news that her poverty-stricken homeland in the Karoo region is next to benefit – South Africa has more than 485 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural shale gas, announces one news reader inside 10 minutes – young filmmaker Jolynn Minnaar decides to find out more. Initially she is optimistic and her aim is to promote greater awareness in her country where fracking is largely a mystery. Then she receives a Skype call from the elusive Mr Gee in Pennsylvania, which fills Minnaar with deep suspicion. She is compelled to start investigating what's happening on the ground, and beneath it, by flying half-way around the world.

That was back in 2011. You could say the whole thing has snowballed since then. A simple question developed into a 10-minute clarion call of a short film, which then evolved into this documentary feature film, Unearthed.

Thoroughout this journey the director was determined to maintain her impartiality, rejecting funding from those with a vested interest, as she explains here. The media communications professional was also very savvy when it came to attracting public interest in the project internationally through Facebook and by attending various meetings, from village gatherings to conferences. Campaigning but also consulting far and wide.

It's the depth of Minnaar's research that is truly extraordinary: over an 18-month period she interviewed "close to 400 people on all sides of the debate – from the heads of multinational energy companies to US senators, hydrogeologists, workers in the field and communities living in drilling areas." The latter are particularly moving, putting a human face on the suffering, which companies such as Shell refuse to acknowledge as being directly linked to fracking despite quite damning evidence here. Then there is the matter of those interviews that were cut short or blocked by non-disclosure agreements. All very suspicious.

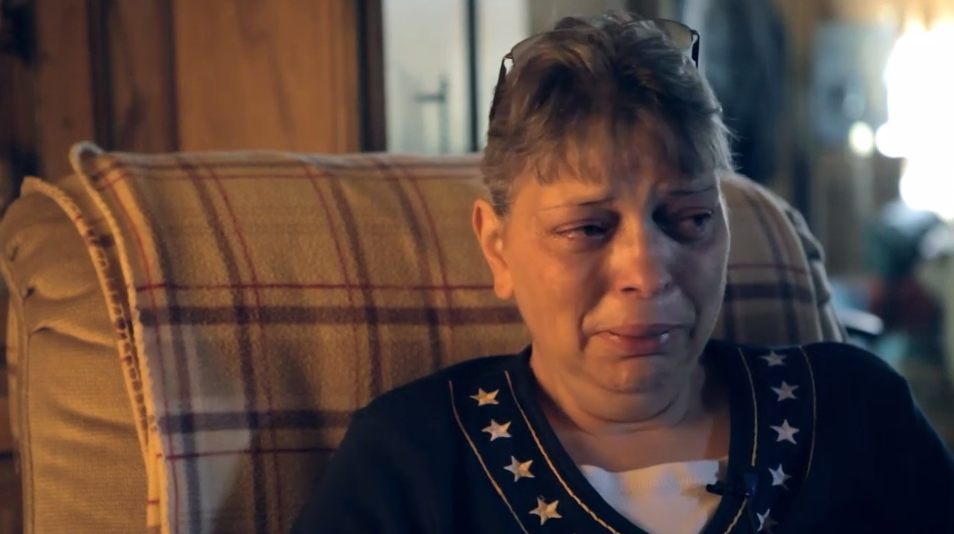

As Minnaar delves deeper, the disturbing revelations begin to take their toll. She visits the McEvoy residence for example, where the following words are uttered as tears begin to fall: "I went into hospital in 2008, the same time as her father. I eventually made it out, he didn't. They tried to accuse me of poisoning my father. Everyone who drank the water became sick. The dog drank the water and he died."

Minnaar's emotionally involved and you are right there with her, feeling the frustration, yearning for justice, perhaps screaming for alternatives. Is this simply another case of big business crushing the little people in the pursuit of profit? The filmmaker plays the role of earnest journalist with a winning combination of naivety and sincerity. Unearthed may not be the first documentary to expose such dark operations – see Josh Fox's Oscar-nominated Gasland – but there's a beating heart here that draws you closer and closer.

There's also a lot of good thinking to ponder. The science and clever animations are convincing, but it is the acute observations that cut deepest; how drillers ultimately can't see where they are going or what precise geology they are dealing with. One strong argument, besides urging caution and calling for further investigation, is the need to direct more funds towards heavy renewable energy investment instead of fossil fuels; something we should have done 30 years ago according to one interviewee in the film. It's a slow transition period and there are obviously logistical challenges, but you have to start somewhere.

This Bloomberg Sustainability Indicators report made grim reading back in 2011, stating that worldwide government subsidies given to the fossil fuel industry one year before were more than six times those earmarked for renewable energy. Fast forward to the year 2030 and this recent New Energy Finance report offers some hope… "By 2030, the world’s power mix will have transformed: from today’s system with two-thirds fossil fuels to one with over half from zero-emission energy sources. Renewables will command over 60% of the 5,579GW of new capacity and 65% of the $7.7 trillion of power investment."

Despite the South African government's staunch determination to start drilling in the Karoo, the film seems to have had some effect as regulations governing fracking will be published next January by the Department of Mineral Resources. The world is watching. For now, it's important to watch films like Unearthed and spread the word because this issue affects us all, not just those in the Karoo or Pennsylvania. Only this week I came across a revived campaign to block the UK government's plan to drill for shale gas under our homes without permission, despite 99% opposition to legal changes.

Perhaps shale gas will help to power future next generations towards a new age of prosperity.

Perhaps reports of opposition to fracking have been greatly exaggerated, as FrackNation director Phelim McAleer claims. "Dimock, Pennsylvania is one place where all journalists reported that everyone hates fracking. Yes, there were 11 families in the village involved in a very lucrative lawsuit with an oil-and-gas company, and the journalists always interviewed them. But they completely ignored a petition signed by 1,500 people in the community who said their water was fine and had not been affected by fracking. What is 11 out of 1,500? Less than 1%. It’s the 99% who support fracking."

Perhaps, as this New Scientist article claims, it's more a case of equipment teething problems rather than the inherent danger of the natural resource itself: "Since these gases are leaking as they are piped to the surface, rather than seeping up through the ground from deep tracking sites, improving the integrity of drill holes and pipelines could curb the problem of water pollution."

Perhaps…

In the meantime, we do as Minnaar has done: keep asking questions and seeking answers.

Unearthed is on tour this winter, stopping off at TedX and IDFA among other events. To find a screening or request one yourself, click here.