Tallinn and I are old friends. I first visited in 2005 to play records, wide-eyed and full of wanderlust, yet completely unsure what to expect having never ventured to the Baltics. A week later I left with many reasons to return, my head spinning with countless adventures and conversations about the past, present and future of this fascinating city.

I also felt reassured because – north, south, east or west – we are closer than we realise. Even in a post-Brexit funk. It could be a mutual respect for family, a belief in community, the call of the dancefloor, a love of art, sharing an ice-cold beer… As familiar as I had become following subsequent visits, it was surprising to see how fast things were changing as I flew in to experience the last few days of Tallinn Music Week (TMW).

Now in its ninth year, the event embodies a very holistic approach to festival programming. One minute you could be moshing to a metal band in an old theatre or heading ‘out to lunch’ with an experimental jazz quartet, and the next … discussing changing patterns of music consumption and curation, debating the city of the future or hearing about ballet dancers rising up from African slums.

Yes, there are 250 bands, artists and music ensembles amassed from more than 30 countries for your pleasure. They definitely know how to party over here. But let’s not forget the films, talks, urban spaces, youth programming and Creative Impact sessions on sustainable development taking place in more than 100 locations within a 20-minute radius of the city centre. It’s compact yet mammoth, like a cross between TED and Brighton’s Great Escape Festival.

Power stations have become powerhouse cultural hubs, cold factories have been transformed into cosy cafés and garages have been “hacked” for gigs, while fine dining experiences rival those of any hip and happening city. Peeter Pihel’s Trash Cooking Dinner, rustled up from food waste, was something special.

Festival founder, Helen Sildna, often talks about “giving new meaning” to things, like rebuilding communities and cities. This is clearly the core imperative of TMW – to see what positive impact a creative community can have on society. In the process, a scene becomes a sector, with a global outlook and collaborative spirit baked in from the day one. Music is like that. It brings us together and opens us up.

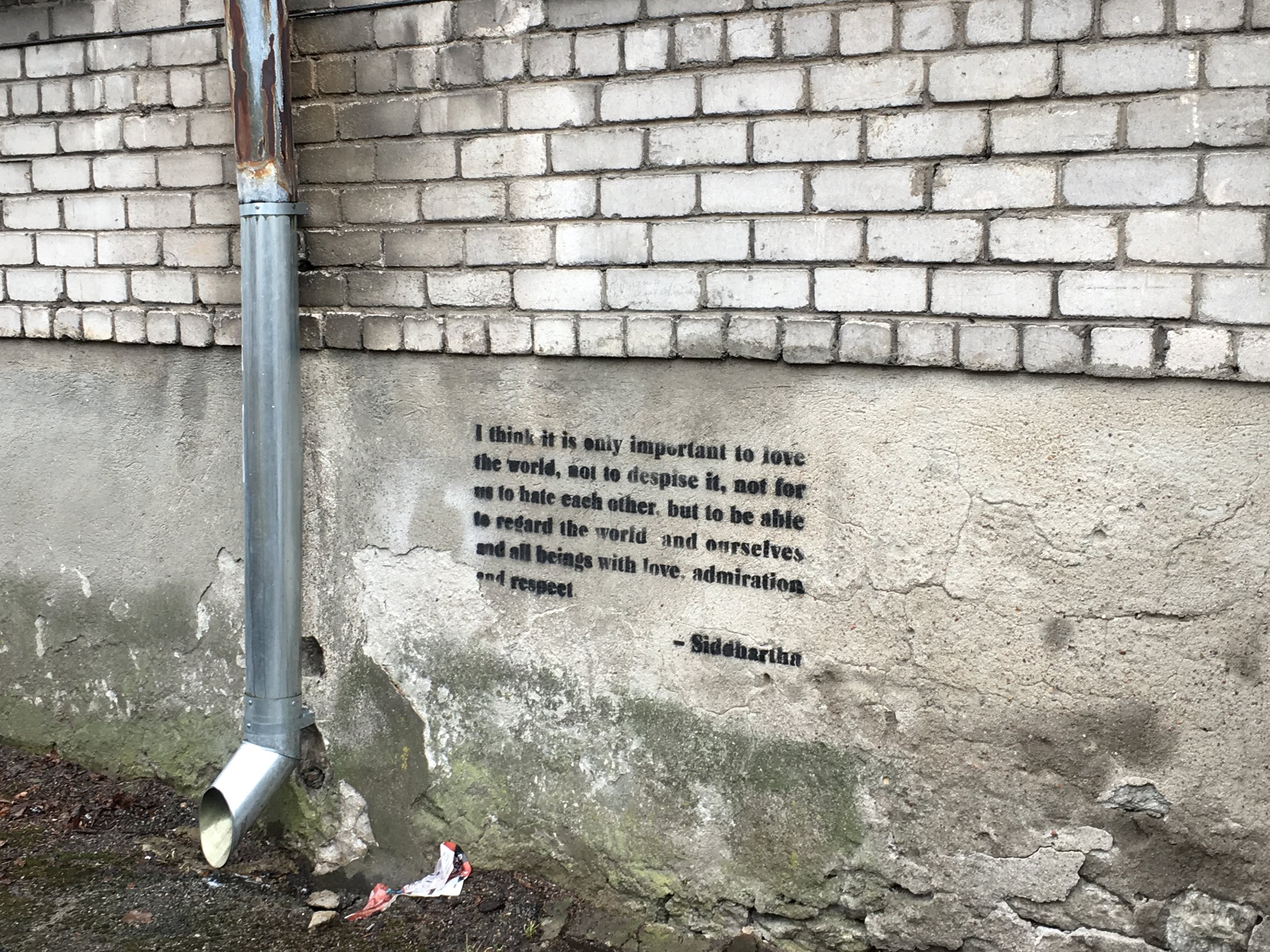

This festival aims “to cross borders” and to be a world without “opposites” or “fences” as Estonia’s president Kersti Kaljulaid stated in her opening speech. But this didn’t happen overnight. It is worth remembering that Estonia only received its independence in 1991, after years of oppression, so it’s been quite a task shifting the mindset at both governmental and ground level.

“People found themselves in a totally new political and economic system,” says Sildna, who sees herself as a public policy strategist as much as a music promoter. “Suddenly people had ownership over things, everything up to ourselves to work out. There was a large process of setting up private ownership. The mentality around things and ‘what it means to be an entrepreneur or an active citizen’ changed dramatically. The same formula had to be brought in to the creative sector.

“As the history was in state-supported culture [as opposed to] independent underground, the same sort of reforms had to run through the creative sector too. The reason why we talk about everyone’s right to freedom of self-expression relies on the same logic – it is not up to the Ministry of Culture to offer judgment of what is worthy and what is not – our cultural and creative policies should be directed towards more opportunities for more.”

By providing the platform for artists and entrepreneurs to show what they can do here, the hope is that they will have more faith in themselves to build a career and make a difference, which is obviously a key consideration for younger generations. “That is the meaning of liberal democracy to me,” she says. “Everyone’s individual right to shape their own future.”

One local musician seizing every opportunity is festival regular Sander Mölder, who I bumped into on Saturday night seven years after our first meeting. " I think TMW has been a huge part of the music scene, both in Tallinn and Estonia. There have been lots of success stories, which are partly or 100% down to TMW: Ewert and the Two Dragons, Maarja Nuut, Noep… Every year it creates a buzz, with bands getting together and actually writing new stuff. Sometimes all the stars align and something great comes out of that."

Saxophonist Maria Lepik also acknowledges the importance of the festival to cash-strapped young musicians seeking a wider audience. "Kreatiivmootor [Lepik's band] had quite a busy year in 2011, and that’s mainly thanks to a successful gig at TMW. Before long, we were playing Brainlove Festival in London, Positivus in Latvia, Popkomm in Berlin, Iceland Airwaves and Waves in Vienna. But it is becoming harder for nameless artists to get a shot. I just hope it doesn't evolve into a traditional music festival, but rather keeps introducing new and fresh ideas, crazy ensembles, surprising sounds…"

The festival is undoubtedly a gateway to the best of the city and beyond. "It is a great chance for local entrepreneurs to show what they can do," says Lepik. "More and more people are coming to Tallinn now. The typical tourist of the past might not have got much further than Old Town. TMW can take them to unusual venues and places they might never see (and that's just as true for locals). Who knows, they may then want to see what else our little country has to offer. "

This wave of optimism around creativity-catalysed, inner-city transformation is not unique to Tallinn. We have seen it in Berlin over the past few years and most recently in Lisbon with places such as the LX Factory, but it’s the pace of change here that’s really exciting. One example is Telliskivi, a revamped northern quarter of the city.

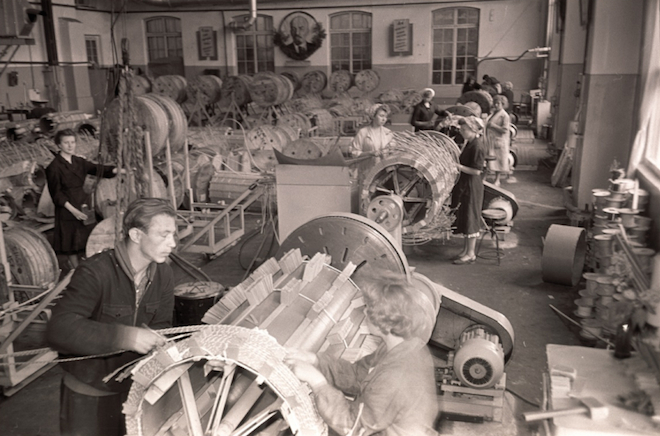

Its founder is Jaanus Juss, a former investment fund manager who had the vision to make a derelict Baltic railway factory and Soviet-era electronics plant into something more than a block of flats. The 40,000 square-metre site was established in 2009 and is now home to 250 companies and around 1,500 professionals including designers, dancers and multi-disciplinary artists.

“This used to be a walled, unsafe area policed by guards with dogs,” says Juss. “Now it’s more like a city, a fertile ground where fresh ideas have a chance to grow. And it’s 100% privately owned, which means we can get things done. That could be offering studios at 50% less than the usual rates, going carbon neutral [which should happen in the next few months] or encouraging people to drink less even if the bar makes a loss. The aim is to have some sort of long-term impact on the community: a cleaner environment, more culture, a wider range of services on offer…”

Juss has another analogy to describe his approach to making Telliskivi, a city that has flourished without the help of local government. “For me, it’s like curating an art exhibition,” he explains. “Every tenant needs to add value to the community. We only tend to give studios to one or two people out of ten. But it’s a democratic process as everything we do here is debated on a closed Facebook group.”

Having check amorphous jazz outfit Fallen Flags at Renard Coffee Shop the night before, the following day I took a quick tour with Juss. We peeked into a few homely meeting spaces and stores, passing through the impressive Vaba Lava performing arts studio and Soltumatu Tantsu Lava contemporary dance space … even sampling some delicious freshly baked bread from Muhu Pagarid along the way.

Apparently recording studios are next on the list, as well as more public events to add to the many that currently happen each year, like this. As if that’s not enough, there are plans to open a similar city that’s twice the size in Riga. You can't help but feel inspired after coming here. As a dark cloud gathers over London and the city continues to work only for the privileged few, could Tallinn be the next stop for frustrated artists and makers?

But back to the music… The downside of having such a packed programme is that visitors are inevitably going to miss out on something; especially if they arrive with only a couple of days to go [note to self]. The best way to tackle TMW is to not plan too much. Submit yourself to serendipity. It's ok to follow the crowd now and again. Their favourite act could become your new favourite act. I fell in with a few seasoned delegates, who took me out of my comfort zone. Random accessible memories include:

· All-girl four-piece Žen generating a swirl of shoegaze-inspired sounds, rich in reverb and undulating guitar lines. Somewhere between My Bloody Valentine and Warpaint.

· Hauschka fiddling with the insides of this piano, inserting foreign objects and whatnot, to the delight and bewilderment of a jam-packed St Olaf’s Guild Hall.

· Finnish group Teksti-TV 666 rockin’ out with (at least) four guitars. Pure head-banging excess. Von Krahl is an interesting venue, an experimental theatre that has been an important artistic hub since the Nineties, at the intersection of folklore, politics and culture.

· The faces of pubescent post-punkers The Homesick during their set at Kultuurilkubi Kelm. Somewhere between angst, indifference and simmering rage. Good energy though..

· Syrian-Filipino MC Chyno winning over the crowd singlehandedly at Sinilind. He had to follow a full-blooded set from local hero Azma, the "Estonian Enimem", and had just finished chomping on a very saucy Hesburger with us. Skills. Credit to TMW for looking further afield, something that Chyno’s manger Anthony Semaan says is a rare occurrence on the European circuit.

· The swagger of Tomm¥ €A$H as he took us for a tour of his “hood” at Maakri 31 garage, in only the second year of outdoor performances at TMW. Voice of a jilted generation? The music is too derivative for my liking (it could be Travis Scott, Young Thug or insert US rapper du jour here). But it’s the visual side that really intrigues me. Surreal and provocative.

· Seeing the pavilion of Balti Jaam train station converted into a Berghain-like techno fortress, complete with trippy visuals. No melody, no mercy, for 36 hours straight. The whole thing felt free, spontaneous, a little naughty. A stark contrast to what’s been happening in London.

· Heading to the design market at Kultuurikatel on a glorious Sunday and hearing the DJ play Tabu Ley’ s Haffi Deo – Congolese pop house with an undeniable almost spiritual joy. Once an obscurity, then a staple of London DJs such as Charlie Bones, now a bridge stretching a 1,000 miles and beyond.

· Our Night Tzar Amy Lamé fighting for the right to party in a heated exchange with a local politician, who described nightlife as “a pipe dream”. Instead, he encouraged local government to focus on providing basic public services. And presumably punishing Tallinn residents if they are not in bed by 9pm having done their homework… Lamé countered that London’s nightlife is worth more than £26 billion each year. She encouraged local government to “to put culture into everything that’s built here. And soundproof it.”

Congratulations to Helen Sildna and her team on a very successful event. Almost 37,000 people attended during the week, in a city with little more than 440,000 residents. I have been to the odd festival before and TMW is in the premier league when it comes to ambition and atmosphere.

A festival should be more than just a party, concert or trade show. It’s about an exchange, new experiences with strangers… a break from the norm. I will be heading back for a full week of stimulation next year.