Gus Van Sant is perhaps best known as the director of Oscar-winning Good Will Hunting. A crowdpleaser that focuses on the relationship between a gifted but troubled young man (Matt Damon) and his therapist (Robin Williams), and his reluctance to break free from the cocoon of small-town Southie in Boston.

But when you consider this against some of his riskier projects – Gerry with its barely speaking two-person cast wandering the desert, Elephant recalling the horror of Columbine, that shot-for-shot remake of Psycho or “forgery” as Van Sant dubs it – we get a very different picture of the filmmaker. The Art of Making Movies is as coherent and linear an appraisal of his work as you will find, and yet it also reminds us that this is someone who rarely sticks to the script or goes by the book.

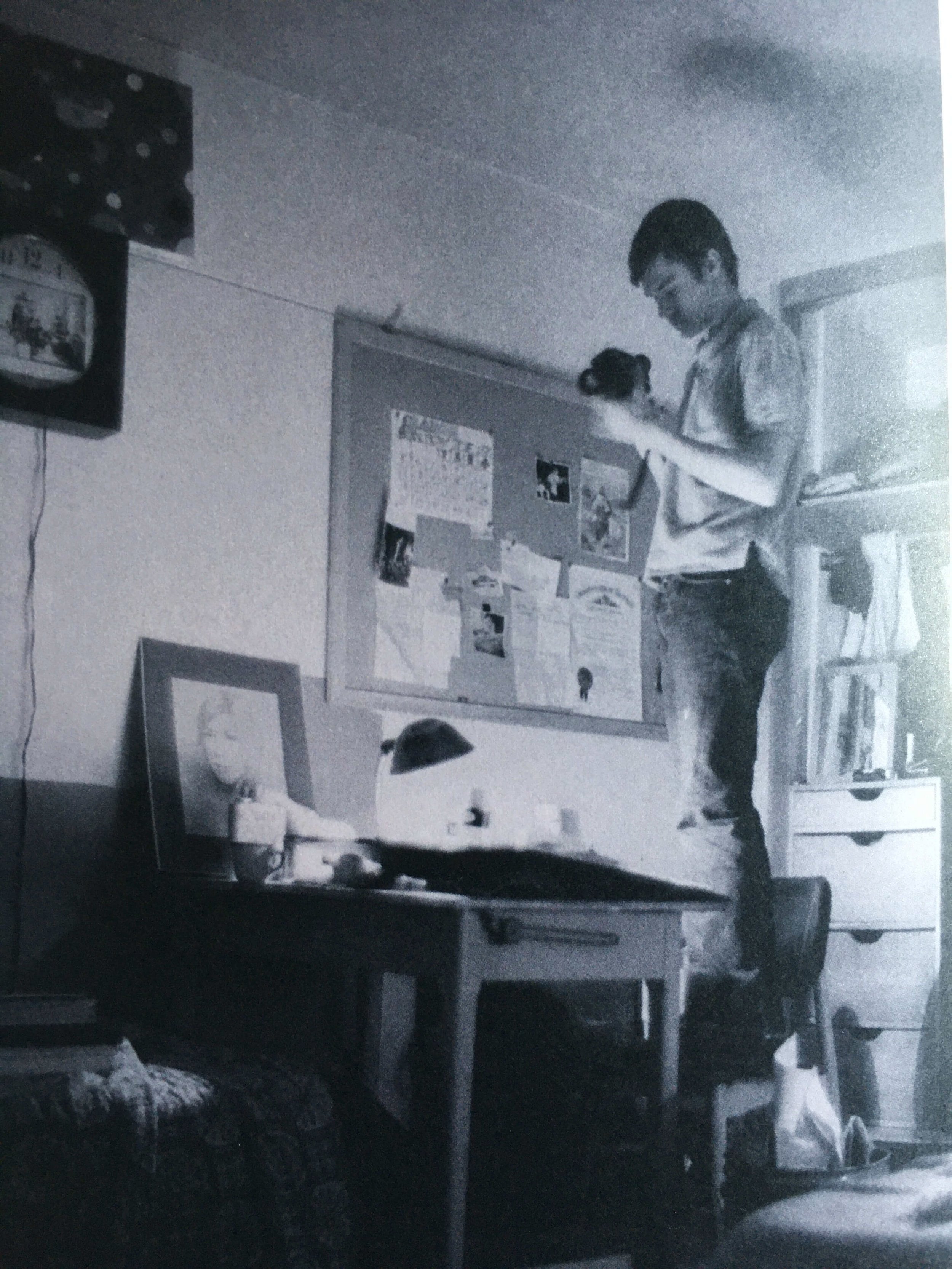

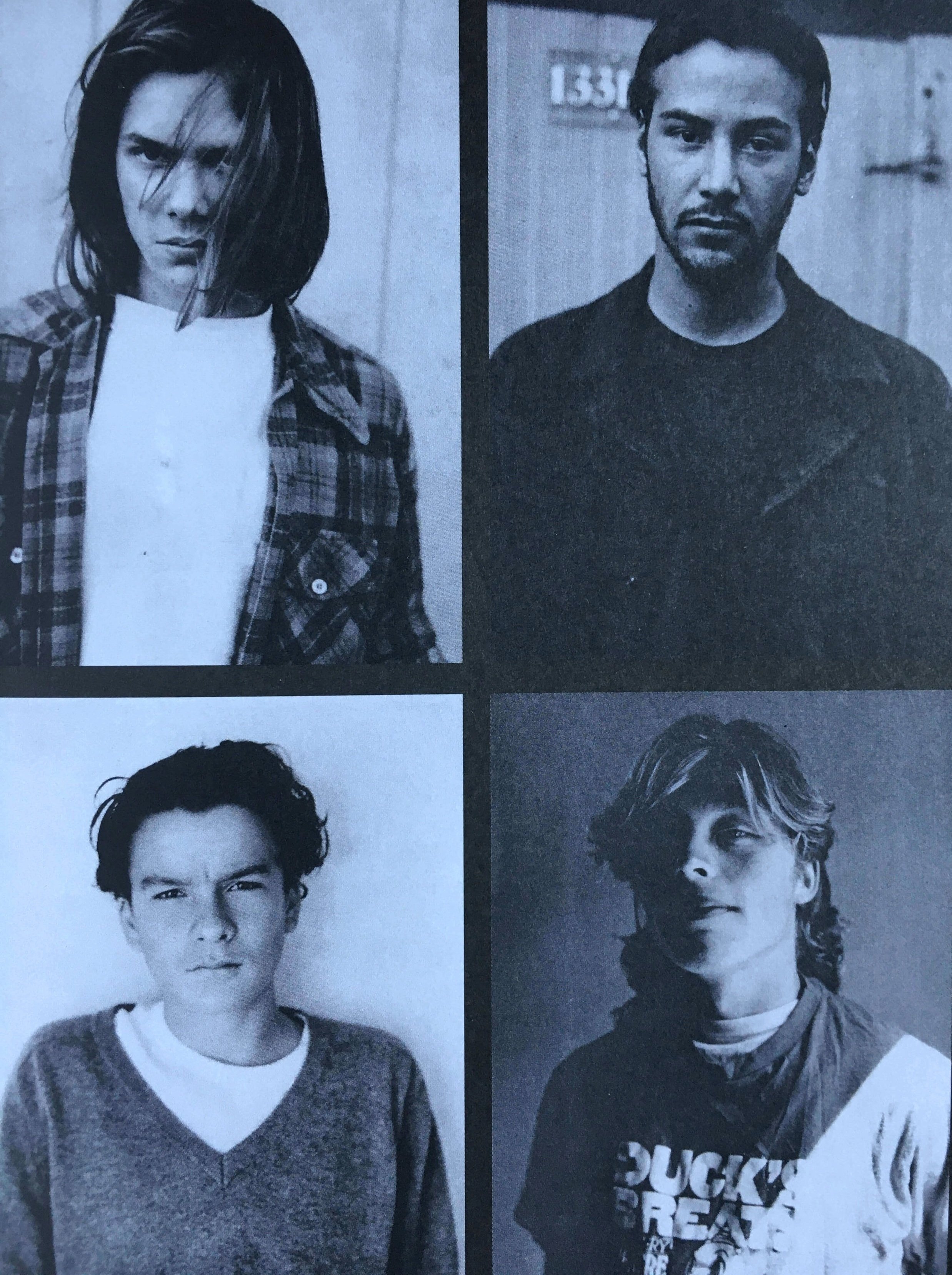

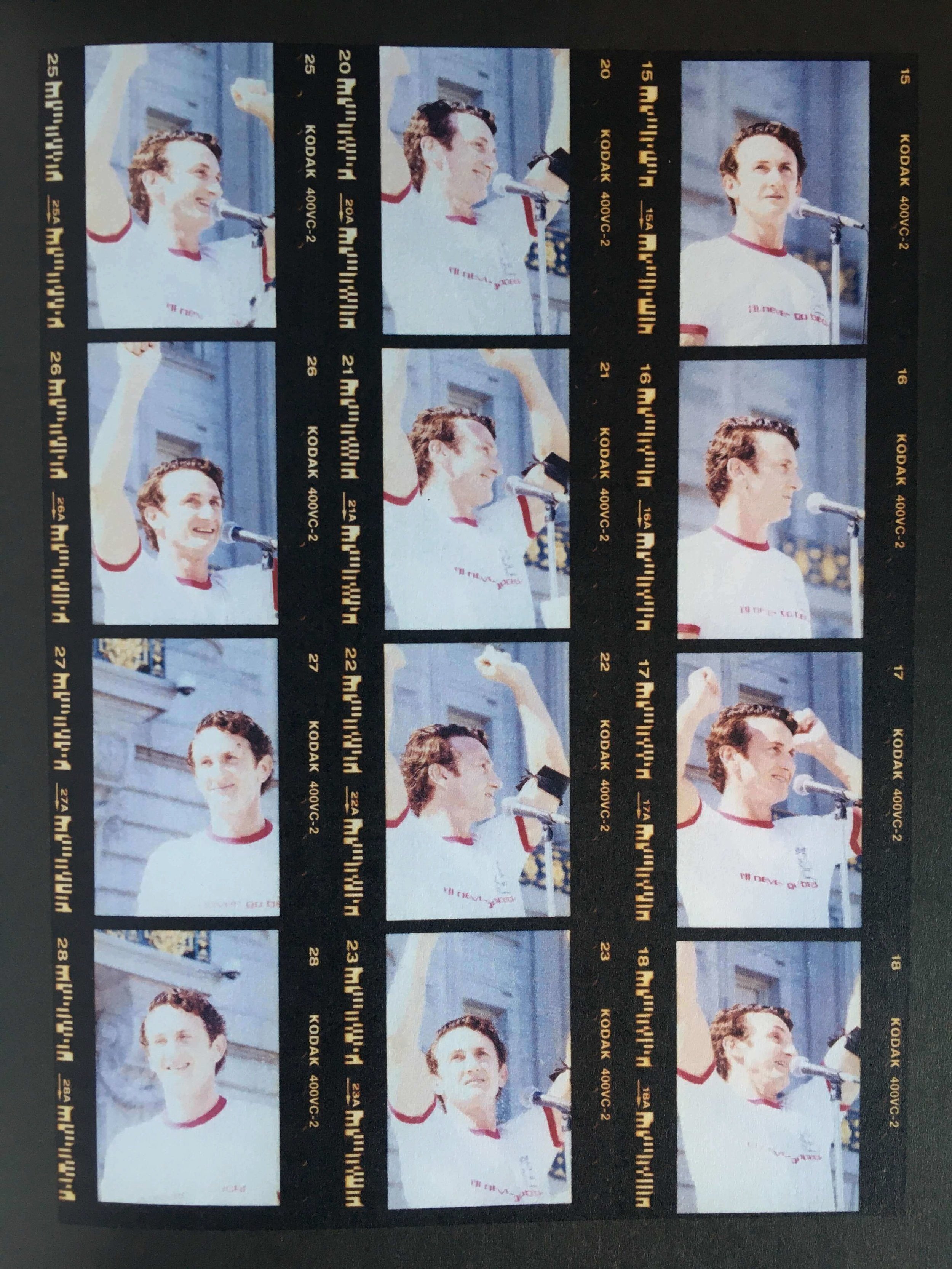

Van Sant is first and foremost an artist, a painter and photographer (feast your eyes on those screen-test Polaroids) who came to film through his obsession with the likes of Kenneth Anger and Alejandro Jodorowsky. In cinema, he hoped to achieve what literature could do in a line. That is, to invite contradiction by evoking one particular time while speaking from another.

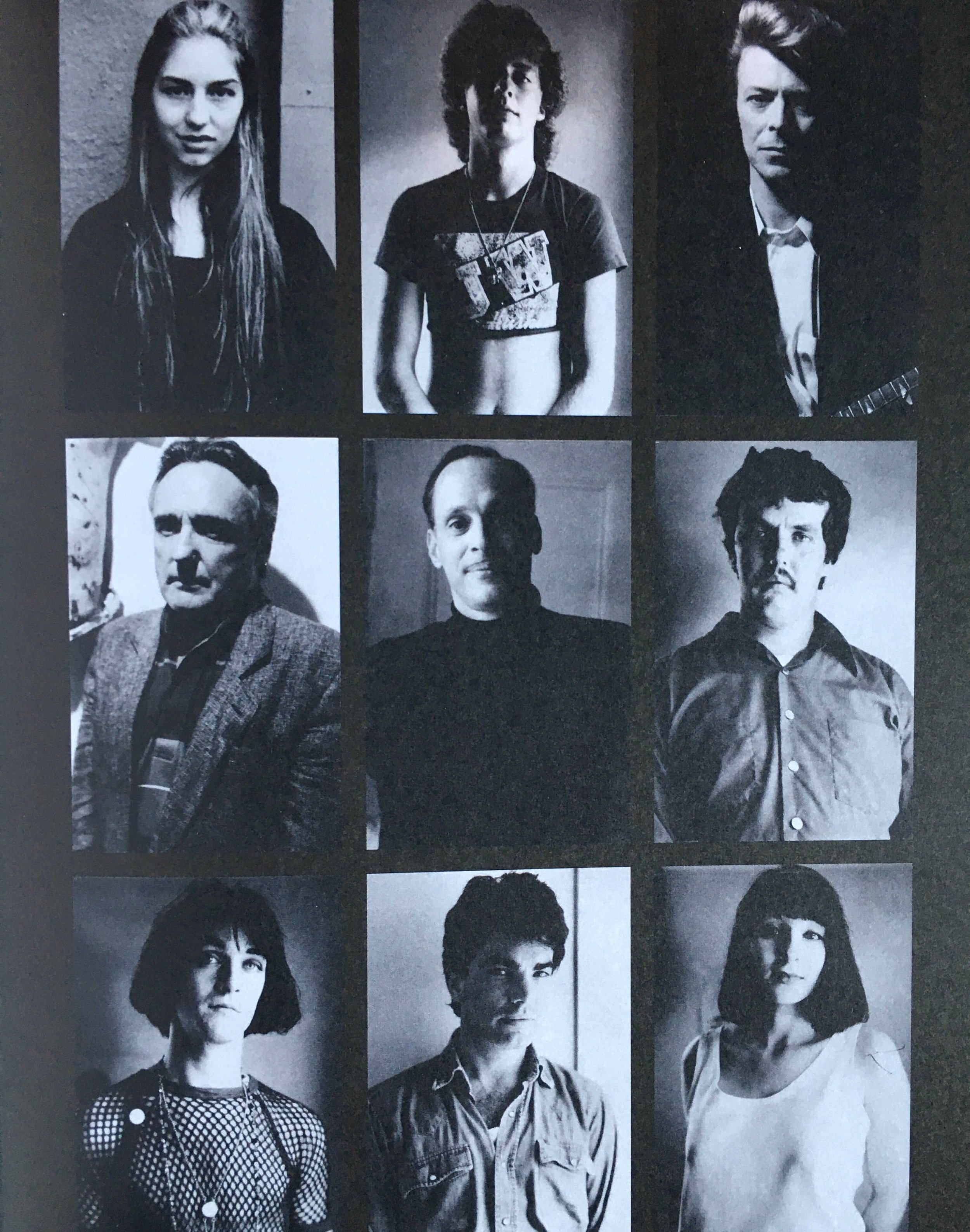

Then, to construct open-ended and abstract worlds around peripheral figures in society – the outsiders, outcasts, drifters, hustlers, loners. Often deferring to amateurs who he feels are best placed to convey their reality as a role (whether they be supporting cast members in My Own Private Idaho or leads in Paranoid Park and Finding Forrester).

His default mode is poetry and suggestion rather than exposition or resolution. His practice is informed by intuition, spontaneity and feeling, then fired by constraints. For a director whose credo has been “continuity is the enemy”, his abstract impression of cinema shouldn’t really work. But it has … and it probably will again.

It’s a bold move to attempt to make the banal or mundane into something more profound and feature-length. Gerry was tedious but Elephant felt far more compelling to me in how it resisted our need for quick answers to a burning question. By casting a detached, non-judgemental gaze, the film held a mirror to a confused, contradictory society as writer Kayta Tylevich puts it in the book.

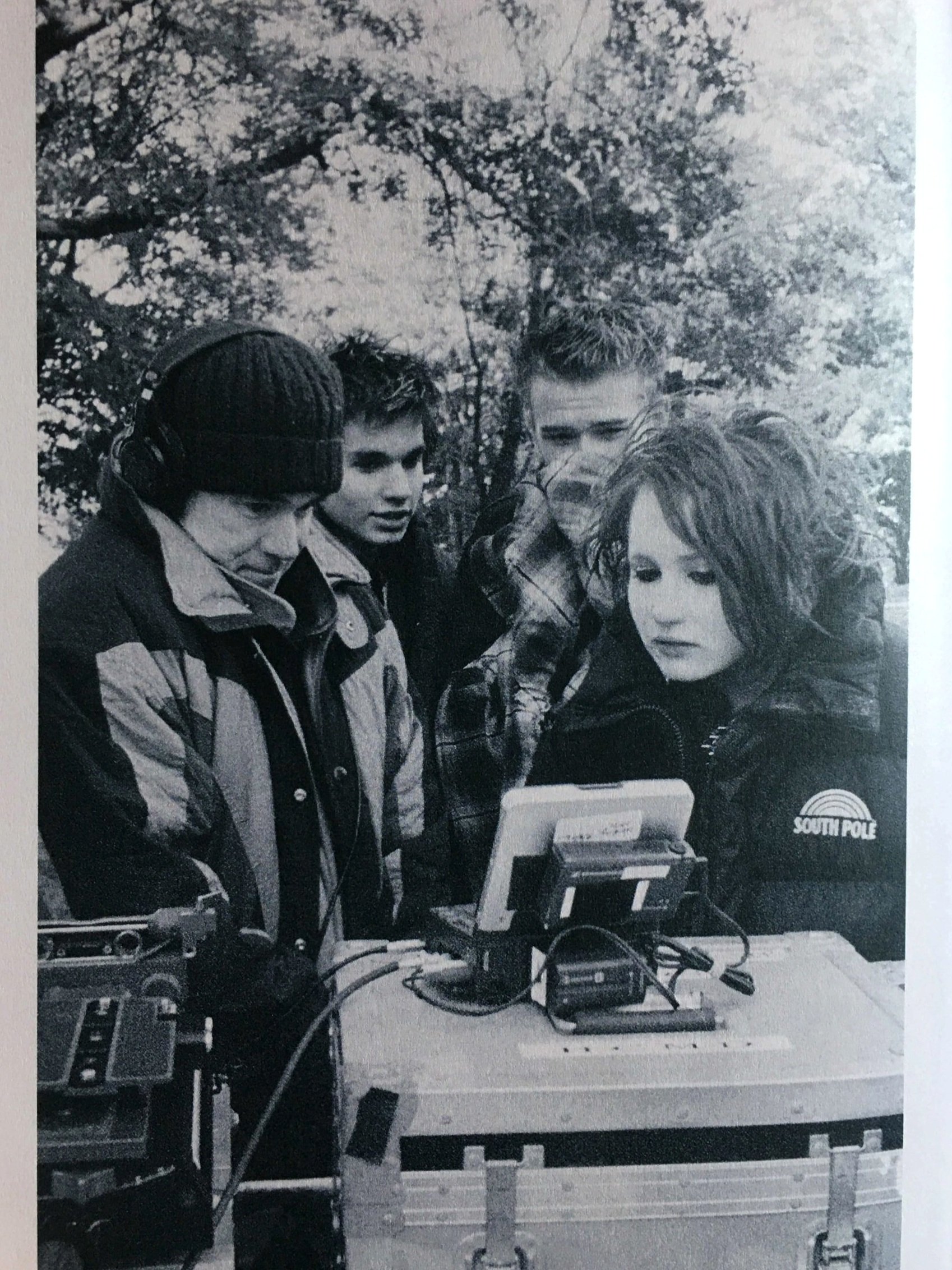

Acclaimed cinematographer and Wong Kar Wai collaborator Christopher Doyle has worked with Van Sant on two projects: Psycho and Paranoid Park. He describes the director’s pursuit of purity like this. “How do we get down to no interference? How do we get down to a point where the film is making itself? We don’t add lights, we remove lights. We remove the obstacle. Get rid of shit and something true will shine through. Gus creates the construct, he creates the architecture. And the details take care of themselves.”

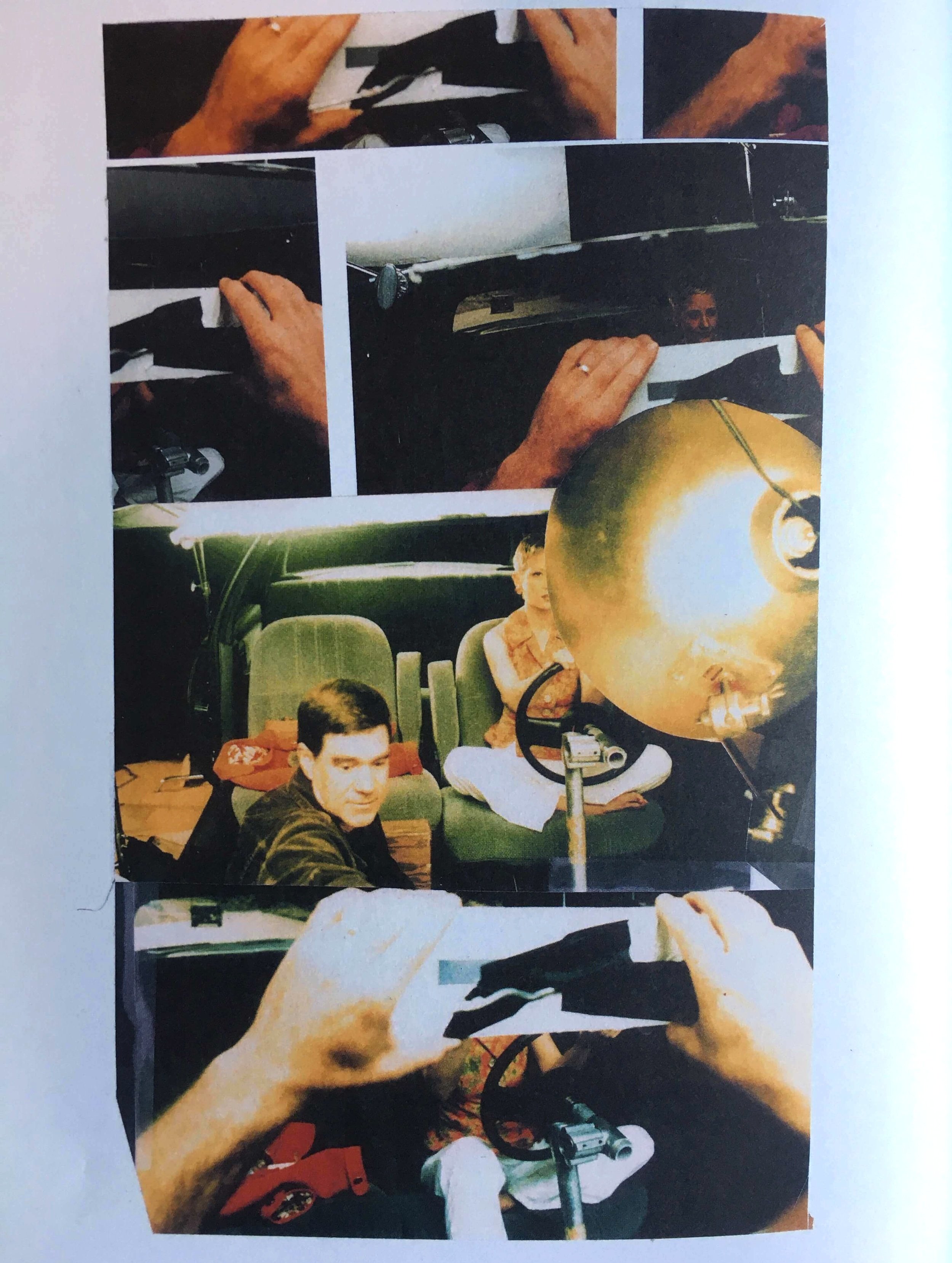

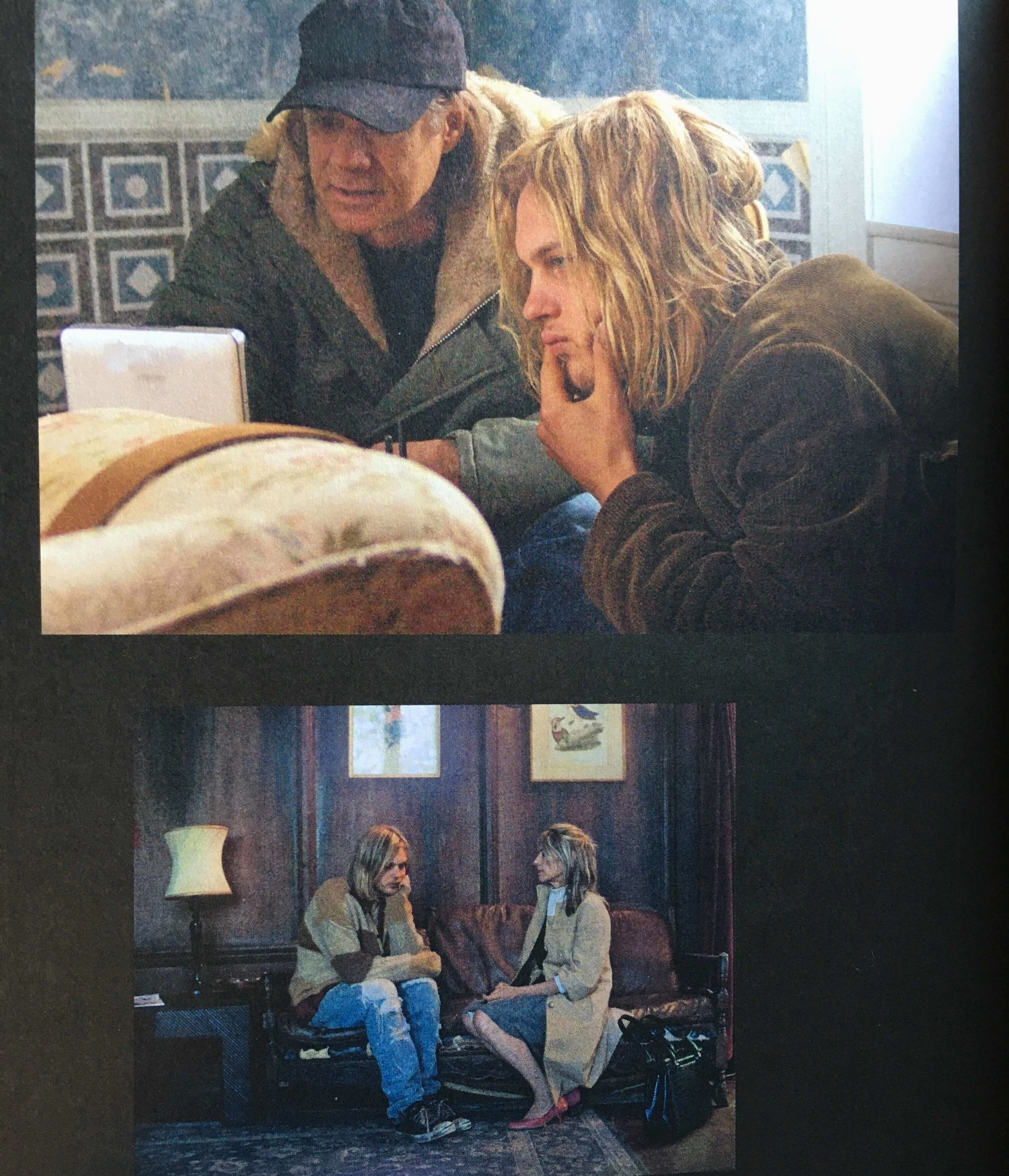

There are lots of tasty bits of trivia to satisfy movie fans, most of them confirming Van Sant’s experimental, instinctive nature and how unusual additions and omissions allow thoughts to flower in our minds. Take Ricky Jay’s detective in Last Days, for instance. How he makes up the dialogue in the car about Chinese magician Ching Ling Foo and his rivalry with American Billy Robinson who apparently ripped off Foo’s act (as Chung Ling Soo).

We learn that Soo died by misadventure, specifically catching a bullet in his mouth on stage. Eerie echoes of rumours flying around the death of Kurt Cobain, on whom lead character Blake (Michael Pitt) is loosely based. That car journey hints at the subtle dark humour that has laced several of his projects and the ordinariness of events that often proceeds something as catastrophic as suicide.

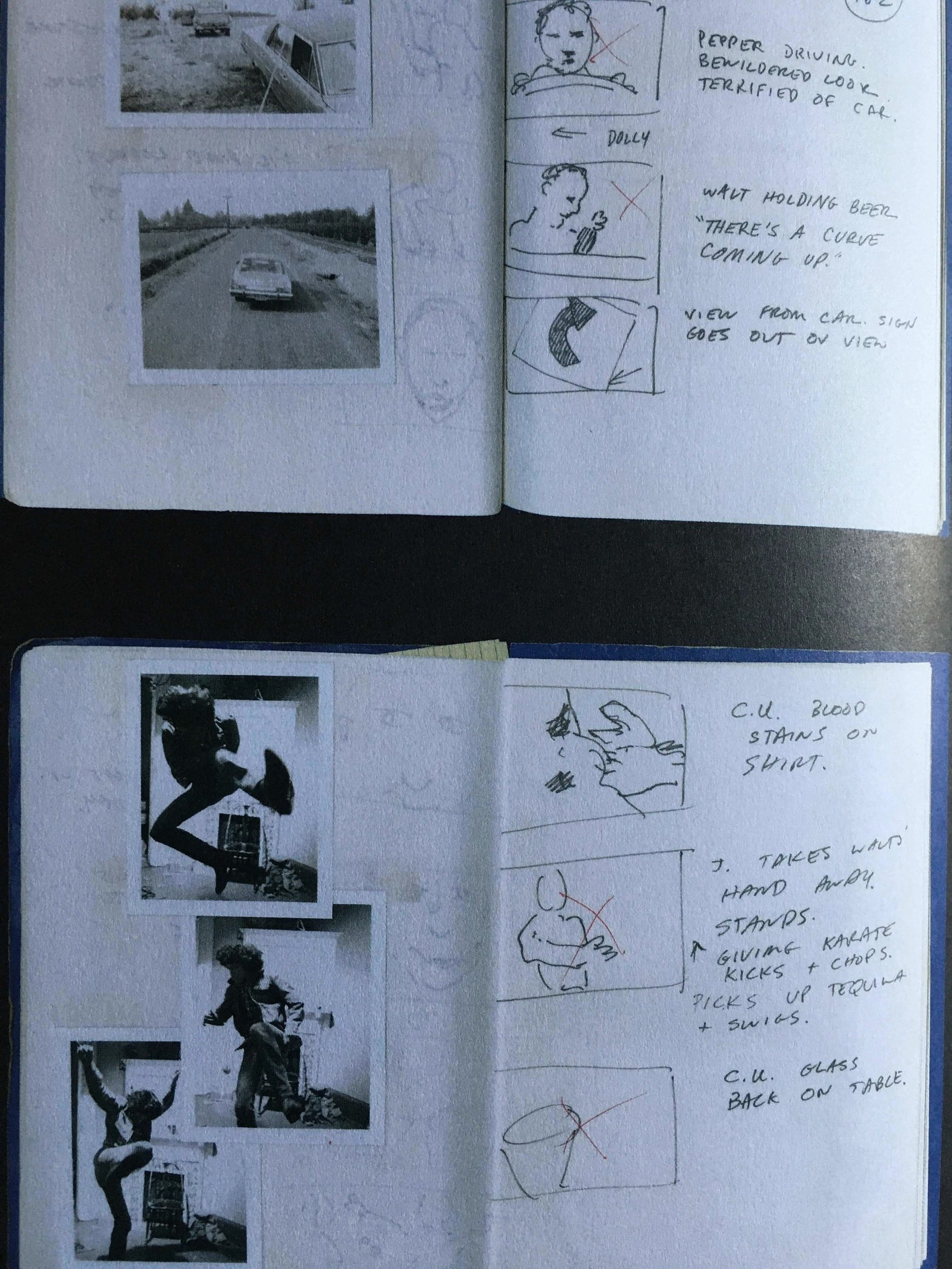

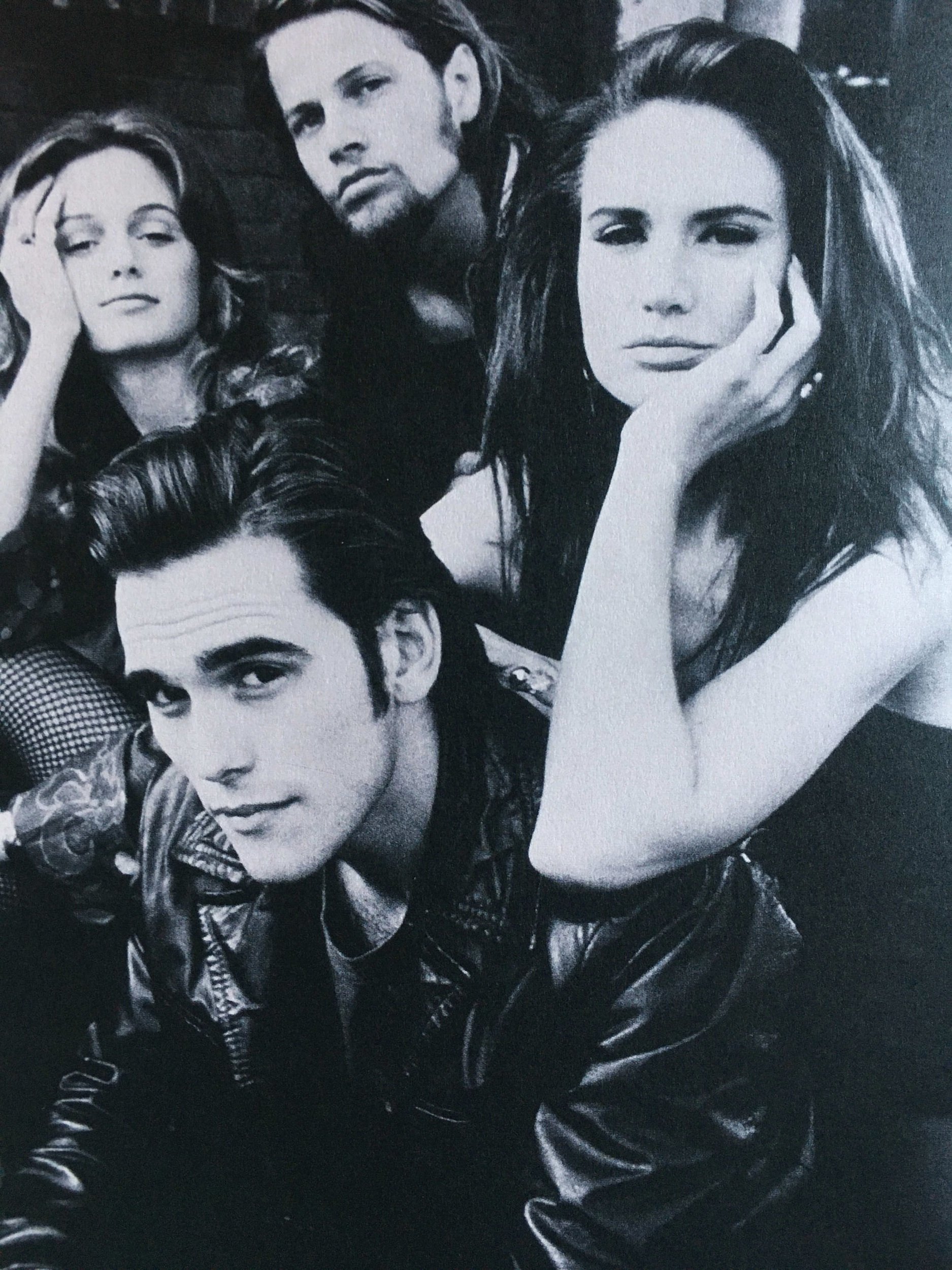

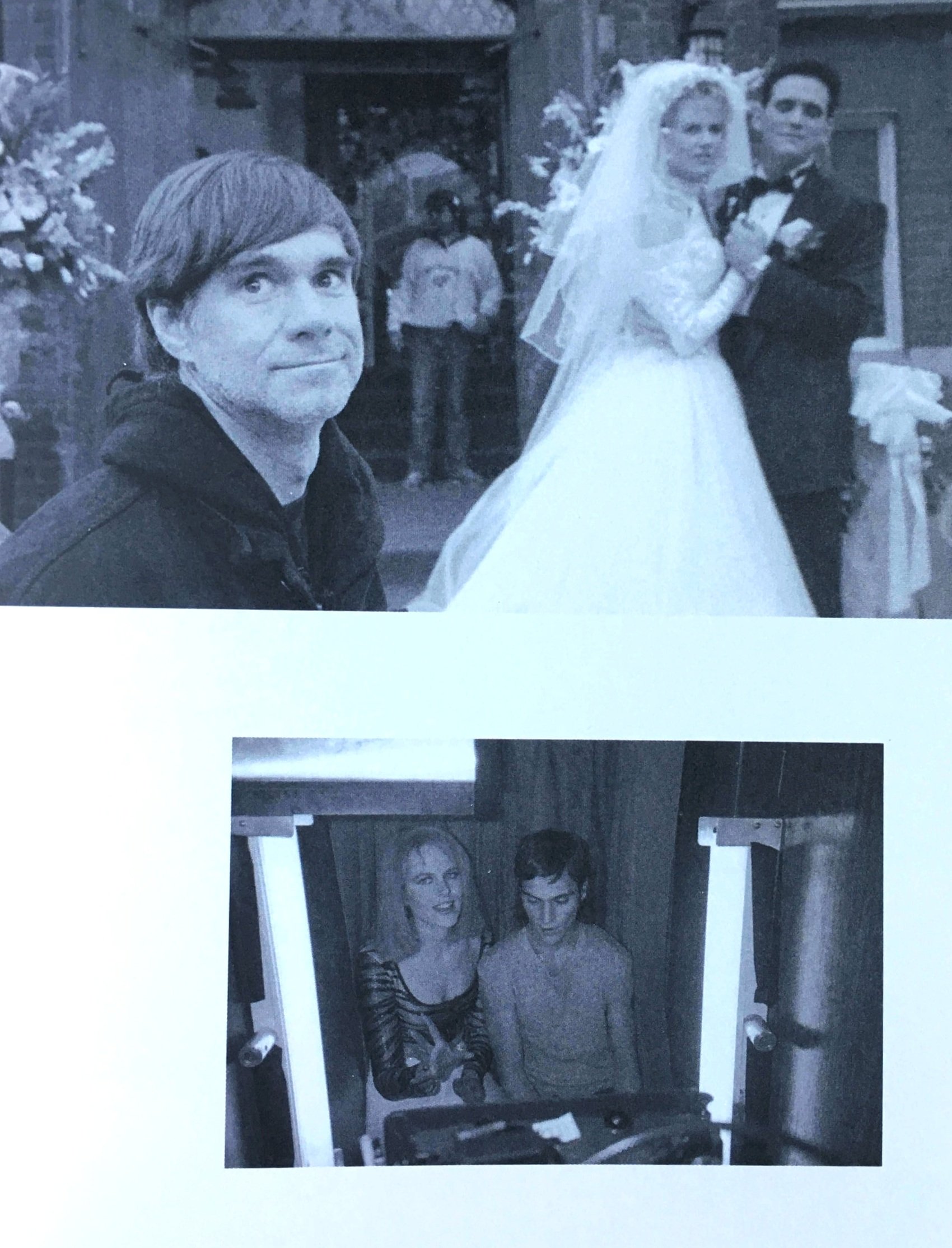

In My Own Private Idaho, that poignant campfire scene between Mike (River Phoenix) and Scott (Keanu Reeves) almost didn’t happen. In the first script, Mike was supposed to suggest they have sex out of sheer boredom. “Sex had become something he traded unsentimentally since love had long become distorted to him,” thought the director. But Phoenix felt that was too frivolous. Van Sant stepped aside and Phoenix added six pages, drawing out Mike’s longing for intimacy and romance, and challenging Scott’s assertion that “two guys can’t love each other”. That scene became one of the seminal moments in 90’s queer cinema and a watershed in Hollywood.

As Van Sant's profile has grown, rather than getting comfortable he's settled into the role of antagonist, rarely doing what is expected of him. Undeterred by an aborted attempt to adapt Victor Bockris’ biography of Andy Warhol, which would have starred Phoenix as the Pope of Pop, he was recently commissioned to direct a musical about the artist featuring a Portuguese cast speaking in English. Whatever next…

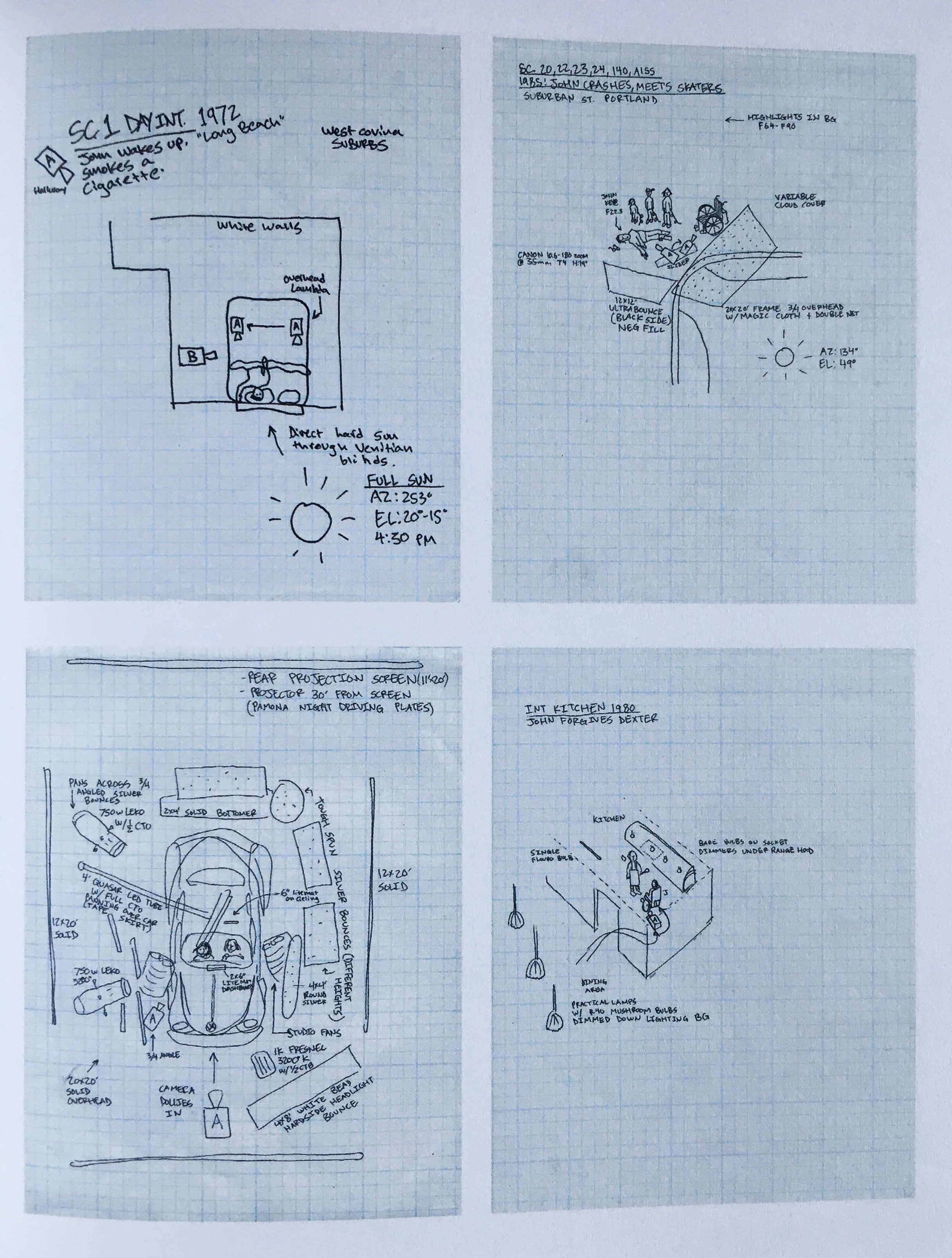

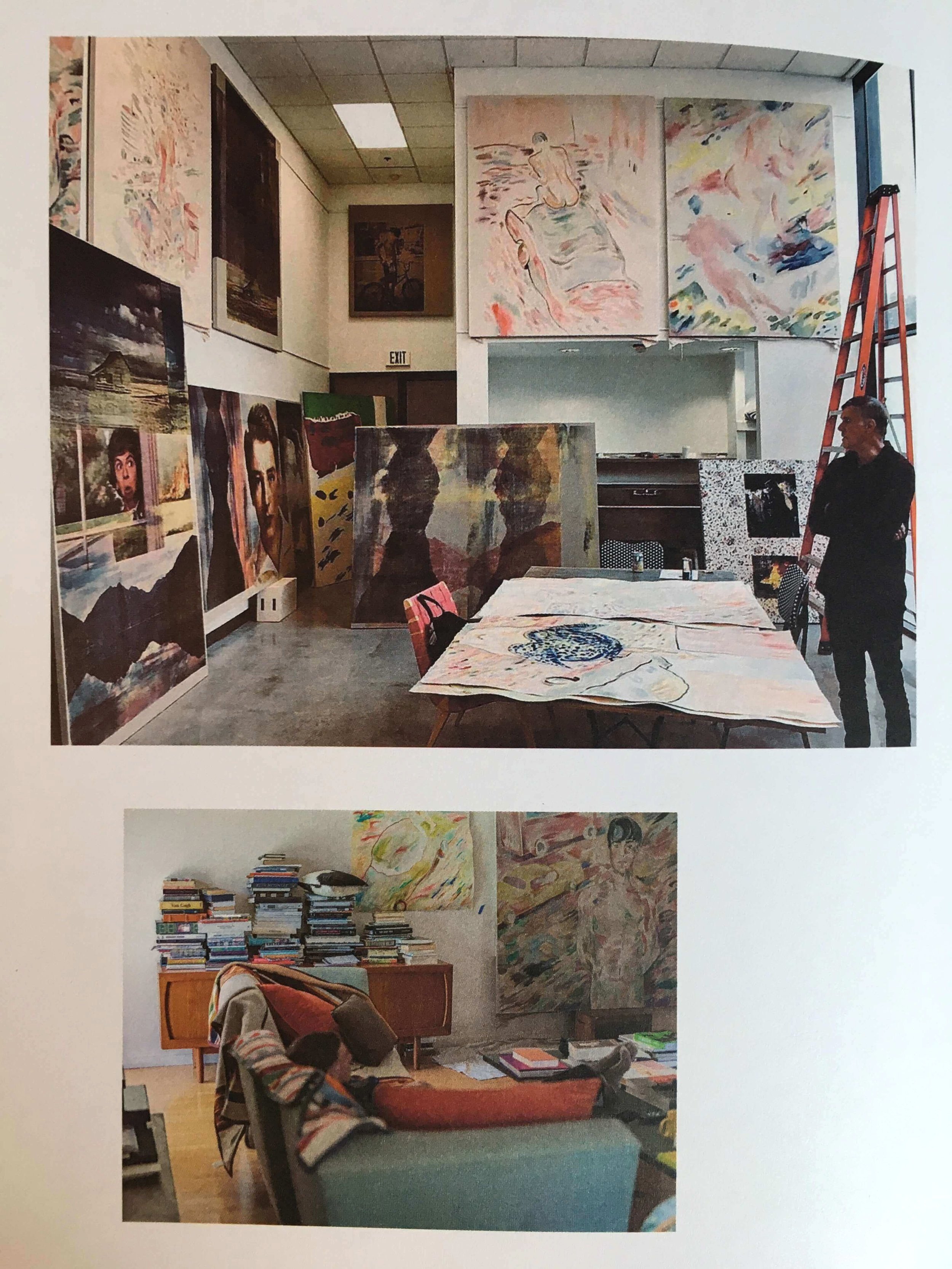

This book is an enticing commentary on his career up to 2020 and will be of interest to anyone that appreciates art and cinema, even if they aren't that into Van Sant's films. The director pulls us into studio meetings where, invariably, he frustrates and resolves to stand by his vision. He puts us on set as if his films are taking shape at that moment, offering sharp recollections beside vivid photos and storyboards.

In conversation with Tylevich, he is also able to look back with a newfound perspective, usually through the prism of art and with an enduring aversion to the conventional or literal. “I either try to be out of control or never really feel like I am.”