A short story I wrote during one of the recent mentoring sessions with the Ministry of Stories and finished off later. The kids at Morpeth Secondary School in East London were working on their own story based in a world they had imagined together. It’s only fair that the mentors also put pen to paper. I went somewhere completely different.

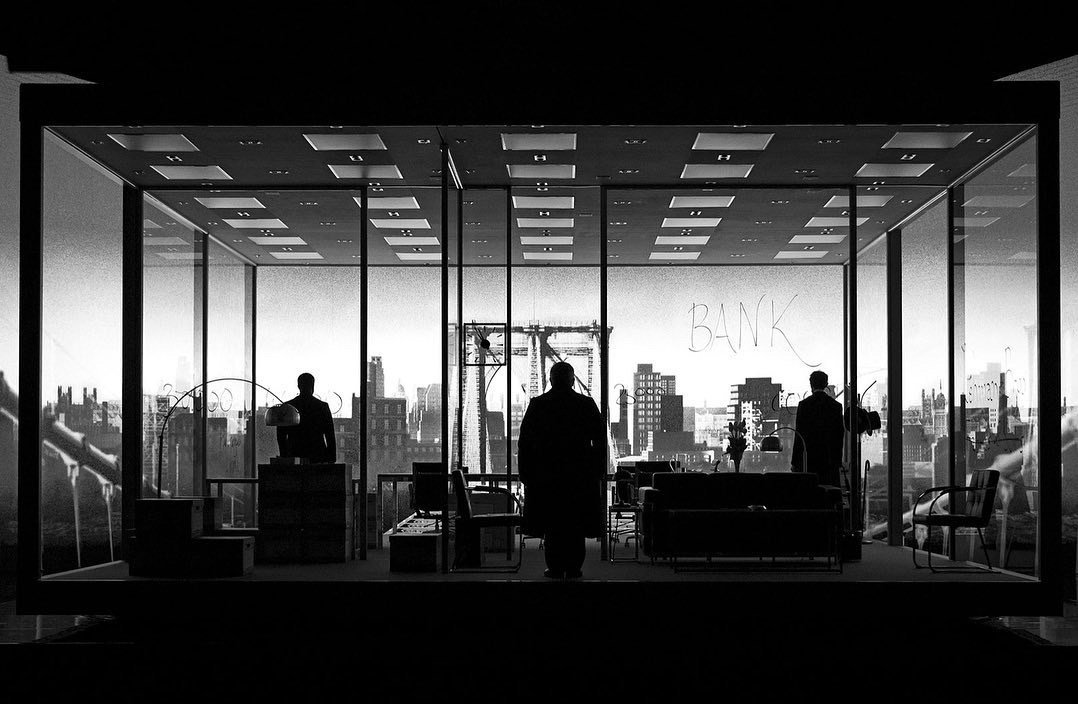

Artwork generated using DALL-E and the prompt “Figurative painting of an elderly dark-skinned man flying on a wheelchair with a fire extinguisher attached to the back of it.” Or a variation of that.

Dedicated to any elders who spend far too much time in and out of the hospital and long for adventure.

***

Monty glanced at his bashed-up watch and thought … it’s now or never. No one had patrolled the corridor for at least an hour.

Even a forgetful old codger like him could tell by the pause in flat-footed steps that would echo day and night. Thuds so loud, it was as if they were made by ogres … with the toxic breath to match.

“Monty, you can do this,” he told himself, all in a dither. “Think about all those nasty things they say under their breath – waste of space, always complaining, someone put him out of his misery.”

He remembered their scolding stares, like hot pokers through the soul. The sludge they would dish out and throw in front of him, rancid and lukewarm.

This was no way for a weary pensioner to be spending his golden years, confined to this decrepit hope-drain of a ward somewhere in the barren underworld of Forelornmore. The place where they put most wrinklies out to wilt until they decompose like neglected plants.

His beloved Amina, by Monty’s side for half his life, always said, “When the time comes to go it alone, always remember how we used to throw caution to the wind. Roll the fluffy dice. Pull a sharp handbrake turn left. Suck in a big ol’gust of chance.

“Your body may not be willing, but show that body who’s boss. Promise me you won’t waste away in some dungeon like a geriatric who spends their days killing time and agonising about their health. Television on only for background noise. ‘We’ll see how it goes’ being your stock answer to everything. But it never does.”

That was the crux of it. Monty used to be one of those folk. It was Amina who changed everything, shaking up his bag of bones and helping him to find newfound awe in unexpected places. A walk in the park, a lucky dip in the market, a wrong turn on the way home.

Now look at him, stirring sludge in his rusty wheelchair. Confined to it. And popping pills he didn’t even need.

He closed his eyes and began to sift through his memories, trying to find the best of himself to feed on, as if to summon the person he needed to be once again.

Just then, a great force began to swell from his temples and along his spine, coursing and meandering down to his fingers and toes.

It felt like the most peculiar migraine, sensational and overwhelming in a good way. And like that, Monty began to make a run for it. Well, more of a stop-start roll but he soon built up momentum.

Suddenly, a door swung open at the other end of the corridor. He pulled up and shuddered. Monty recognised that sound. It was the unmistakable stomp of the nightwatchman Mr Astley – “Ghastly” to all the ‘inmates’.

He carried this ridiculously enormous truncheon and smelled of raw onion soup with flakes of mould. Catch a whiff of him and you’ll lose a year, they would say.

Monty began to panic. “What now?”, the ominous dooof-dooof getting louder and louder. Glancing to his left, he spotted a fire extinguisher hanging on the wall.

Without a thought of what could go wrong, which felt so refreshing, he clipped it on his wheelchair and squeezed hard like he was engaging a turbo boost on a racing car, only with a little more mess to clean up.

No … imagine something even bigger. It was like he was engaging thrusters on a rocket. Wheels quickly became surplus to requirements.

“How do you steer this thing?” Monty hadn’t a clue. As it happened, he was heading straight for Ghastly like a stench-seeking missile. The chief ogre snarled, smoke bellowing out of his nostrils as he advanced, undeterred.

Monty rose above him right before impact, scorching a perfect runway through his pathetic excuse for a haircut and blasting open the doors just beyond.

He soared and soared, clipping onto the wing of an airplane bound for who knows where. This mad turn of events would have been quite distressing if they weren’t so exhilarating.

Monty had this giddy smile on his face, broader than it had ever been. His body still tingling like nothing could harm him.

Thoughts of sunny beaches and far-flung islands crossed his mind. Would he make it? Could be survive? It didn’t matter. Forelornmore was squarely in the rear-view mirror now and the future gleamed with possibility for the first time in a long time.

He slipped on his old cash and carry sunglasses, sucked in a big ol’gust of chance and thought, ‘Let’s see how it goes, eh.”