What a special feeling when you bond with a TV show. And I’m not talking small returns like getting your weekly dose of laughs or escapism. I mean the awe-inspiring, mind-bending, occasionally even cathartic kind. To be honest, it’s only happened a handful of times in my life.

Read MoreMasterful fun

Making the BBC the best it can be

Last week I attended a discussion about the future of the Beeb, with a particular focus on the poor level of diversity both on screen and behind the scenes. We challenged the universality of the organisation – the notion of "a BBC for all" – and learned why there should be no taxation without representation for licence fee payers.

The aim was to make a few recommendations to the House of Lords as part of a public consultation on the Royal Charter review, which closes on 8 October. The Royal Charter is the constitutional basis for the corporation. It sets out the public purposes of the BBC, guarantees its independence, and outlines the duties of the Trust and the Executive Board. The current Charter runs until 31 December 2016. What comes next could be dramatically different and set in stone for another ten years. So we need to get it right.

The mission of the BBC has always been “to enrich people’s lives … inform, educate and entertain.” However, given the rapid changes in technology, shifting market forces and media consumption habits, a review is long overdue. That review will explore the evolving purpose, scale and scope of the institution as well as how it’s funded and governed.

I have always felt immense pride in and privilege in being a BBC viewer and listener. The productions are reassuringly world-class, great entertainment and often deeply insightful – from old favourites such as Question Time, Match of the Day, Desert Island Discs and Gilles Peterson’s Worldwide show, to numerous BBC4 arts and culture documentaries and occasional one-offs such as Adam Curtis’ Bitter Lake. I could even live stream the Olympics and Glastonbury on the magnificent iPlayer from the comfort of my lounge. And let’s not forget the countless laughs, both old (The Graham Norton Show) and new (People Just Do Nothing). There's even a show about how bureaucratic and buffoon-laden the BBC is. You will have your own favourites. Strictly Come Dancing, Sherlock, Poldark, The Great British Bake Off, Wolf Hall… The list goes on.

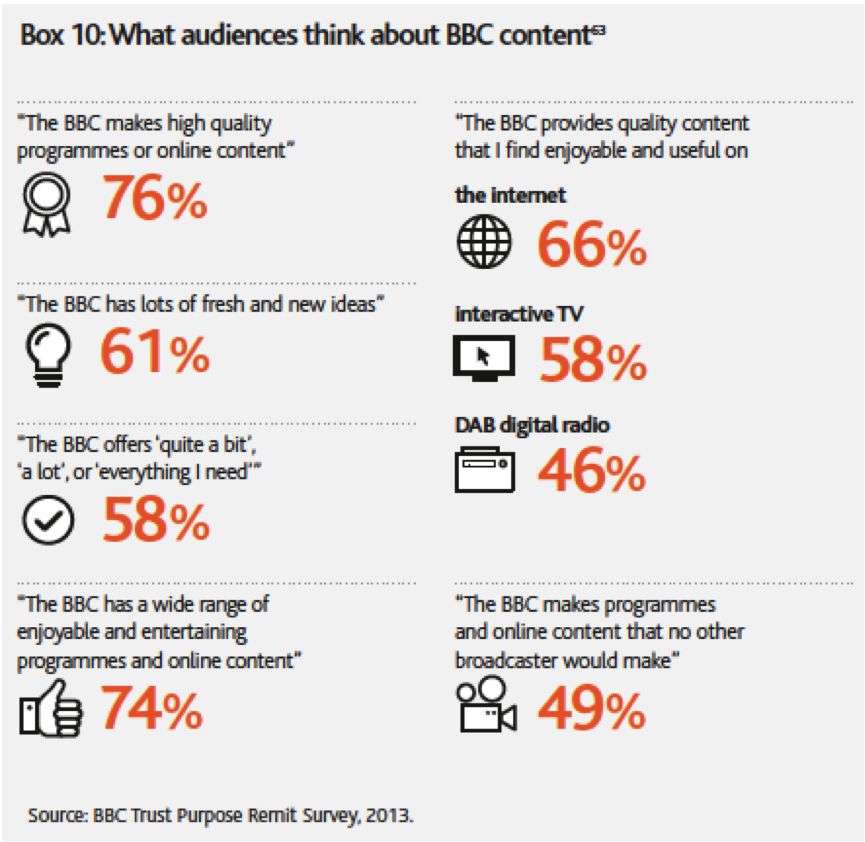

All this, and much more, for £2.80 a week? That is a bargain. Satisfaction levels among the 97% of UK adults using BBC services each week are quite high, although they do vary depending on the region and age group.

But there are challenges, growing pains, a need to adapt… The main issue is budget, with the government forcing the BBC to cover the cost of TV licences for over-75s (that’s around £750 million each year). High-quality, on-demand programming is expensive and not everyone is willing to pay for it, particularly those who say they do watch the BBC. So do you impose a household media levy as in Germany, introduce a tiered subscription model geared to how much we consume, or perhaps a combination? How can you fund a public broadcaster and encourage development over time without diminishing value to the customer or imposing a stealth tax? For one thing, iPlayer on-demand viewers should not be getting a free ride. Regardless of whether the programme is streamed live or watched on catch up, everyone should contribute.

Another issue is the number of people who say they don't feel represented by the Beeb and that is where the figures on BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) talent have been particularly damaging to the public broadcaster. Channel 4 has announced that 20% of its London staff will be BAME by 2020; at Sky it's 20% of all UK on-screen and writing talent before 2016. And at the BBC? A disappointing 15% (on screen) by 2017. This latter target was announced by Director-General Lord Hall in June 2014 as part of a diversity strategy. Other measures include a £2.1 million fund for BAME talent on and off screen to develop new programmes, more training internships, recruiting six Commissioners of the Future and setting up an Independent Diversity Action Group featuring Lenny Henry and Floella Benjamin, among others. But this doesn’t go far enough for the likes of Simon Albury, chair at the Campaign for Broadcasting Equality, who has called for £100m of ring-fenced funding. "Money changes things," he says.

Lord Hall maintains that the BBC is making progress but a quick peek at casts and credits suggests otherwise. Henry, a tireless campaigner on this subject, noted that between 2006 and 2012, the number of black and Asian people working in the industry had gone down by 30.9%. The issue is one of both recruitment and retention: Broadcast Now reported that between 2009 and 2014, BAME resignations at the BBC increased from 8.6% to 16.1%. Henry first appeared on British TV in 1975. Today, his fleetingly autobiographical drama Danny & the Human Zoo is one of the few BAME stories on the BBC. Progress?

It’s important for the flagship BBC One to be setting the right example, which is why Oscar winner Steve McQueen’s forthcoming six-part drama about a West Indian family in London is so exciting. Meanwhile Motown-powered musical drama Stop!, written by Tony Jordan (Eastenders, By Any Means, The Ark), will “reflect the diversity of modern Britain” apparently. What about emerging talent though and even more provocative storytelling?

Clearly, jobs at the BBC should be going to the most promising, suitably experienced and talented candidates regardless of race, gender or sexual orientation. (And that goes for studio guests too, lest we have more car crash TV like this Straight Outta Compton discussion on Newsnight. No wonder viewers have “given up” on the BBC, according to producer Jasmine Botiwala.) But until commissioners, casting agents and other key decision makers can be trusted to better reflect the true breadth of British voices on TV, there will have to be targets across departments. And, presumably, penalties imposed by OFCOM or the DCMS.

The current Royal Charter is quite vague on the subject of diversity. Wade through the weighty tome and you’ll see phrases such as “representing the UK, its nations, regions and communities”, “bringing the UK to the world and the world to the UK” and having Audience Councils “to bring the diverse perspectives of licence fee payers to bear on the work of the Trust”. The broadcasting agreement between the BBC and the secretary of state elaborates further: “The Trust must, amongst other things, seek to ensure that the BBC—

1. (a) reflects and strengthens cultural identities through original content at local, regional and national level, on occasion bringing audiences together for shared experiences; and

2. (b) promotes awareness of different cultures and alternative viewpoints, through content that reflects the lives of different people and different communities within the UK.”

The Audience Councils appear too region-focused and do not sufficiently reflect the cultural nuances within those regions. Culture Secretary John Whittendale acknowledged this fact when delivering his charter review statement in the House of Commons in July: “Variations exist, and there are particular challenges in reaching people from certain ethnic minority backgrounds and in meeting the needs of younger people, who increasingly access content online. Variations exist among the different nations and regions too.”

But back to the question of funding, and one way to bolster the BBC is to “by pushing ourselves more commercially abroad,” in the words of writer and producer Armando Iannucci. During his James MacTaggart Memorial Lecture at the Edinburgh TV Festival he went on to say: "Be more aggressive in selling our shows, through advertising, through proper international subscription channels, freeing up BBC Worldwide to be fully commercial, whatever it takes.”

Lord Hall has acknowledged the need to raise commercial income to supplement the licence fee “so we can invest as much as possible in content for UK audiences.” One example is the forthcoming over-the-top streaming service in the US. He went much further when outlining his vision for the BBC at the Science Museum in September. Presenting his “open platform for creativity”, Hall announced a partnership with local and regional news organisations (funded by cuts to other departments), and advocated an Ideas Service (presumably an echo of the World Service) where the BBC hosts content from leading cultural institutions such as the British Museum and the Royal Shakespeare Company. He also implied that WoCC (Window of Creative Competition) quotas would be relaxed, allowing more independent producers to bid for BBC commissions beyond the current minimum of 25%. In theory that would mean greater flexibility and diversity in TV production. In theory.

His vision garnered mixed reactions. The government has cautioned against placing too great a burden on BBC Worldwide to generate extra revenue for fear of prioritising global commercial appeal before investment in public service content for UK audiences. The Mirror emphasised the huge competition for today’s viewers (between 1994 and 2015 the number of available channels has risen from 61 to 536) and the importance of the BBC to the UK economy. “The money the BBC spends on actors, cameramen, sets, equipment, technical experts and many other areas means more private sector jobs are created and more small businesses are sustained," we're told. "A recent report showed that the BBC was responsible for spending £2.2bn in the UK’s creative industries – with around £450m going straight to small businesses. This helps Britain build a TV industry to rival any in the world. It helps the UK develop some of the world’s best actors, cameramen, and directors.”

In the Guardian, Ashley Highfield, the vice chairman of the News Media Association and chief executive of regional publisher Johnston Press, said: “It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the BBC’s proposal … [is] anything other than BBC expansion into local news provision and recruitment of more BBC local journalists through the back door.”

Innovation charity Nesta gave a more pragmatic and favourable reading, echoing Hall’s tone of evolution not revolution. “The central argument is that the BBC needs to add to its historic mission of educating, informing and entertaining, an additional goal of empowering – using its resources to energise a surrounding ecology of other creators and providers."

Few can doubt Lord Hall’s dedication to the BBC and its founding principles. He genuinely wants to make the corporation more efficient and to serve audiences better through more bespoke and portable content. We should all put a hand in our pocket if we want to reap the benefits. The real challenge will be to make BBC programming more reflective of modern multicultural Britain – complex, nuanced, surprising – one that’s concerned with a whole lot more than cakes and costumes and celebrities in and around the capital. It's about building trust. Otherwise viewers, particularly the 16-24s, will simply switch off and turn to alternatives such as YouTube, Vice and Netflix. Comedy and drama are two areas that require attention.

The loss of BBC Three as a linear broadcast is regretful but the right decision given its core audience's viewing habits and the £50m saving. Perhaps in a new online-only guise, the channel that gave us Little Britain, The Mighty Boosh and a host of other cult hits, will find its way into the lives of tech-obsessed 16-24s, quickly building a following and helping to nudge new talent into prime-time mainstream. YouTube can help to identify shows and concepts that will capture the public's imagination, as Sky have found with Baby Isako's Venus v Mars. There is such much talent out there. Why isn't the BBC investing in confident young voices like director Cecile Emeke?

BBC Taster is a good attempt to allow the public to influence programming but they could be involved even earlier in the creative process. BBC Raw allows young talent to use media to confront issues that matter to them but the project could benefit from better promotion. A golden opportunity awaits to make the BBC a true reflection of the best of British. The time is now.

Have you say here or email BBCCharterReviewConsultation@culture.gov.uk before 8 October.

What the music industry can learn from TV

Earlier this week the Daily Beast published an article about the contrast in fortunes between the TV and music industries, and how one can learn from the other in five ways. They are:

1. Target adults, not kids.

“HBO realized that the dumbing down of network TV left a large group of consumers under-served, namely sophisticated grown-ups—and these were the same people with the most disposable income to spend on entertainment.”

2. Embrace complexity.

“Complexity appeals to the sophisticated grown-ups mentioned above. But also, more complex content inspires repeated listenings and greater long-term loyalty. The subscription TV networks have figured this out. Meanwhile the music industry is hoping that simple songs … will solve their problems. They won’t.”

3. Improve the technology.

“Television has gone hi-tech with big screens, crystal clear pictures, and concert hall audio. Music is the only branch of the entertainment world to embrace progressively inferior technologies. Movie theaters have upgraded their experience. Video games have achieved unprecedented standards of visual quality, far beyond what the inventors of Pong and Pac-Man ever dreamed of. But music devices sound worse than they did a half-century ago.”

4. Resist tired formulas.

“Every one of the old shows suffered from the same obvious problem: you could predict how the story would end even before it started, so why watch at all? But the beauty of the smart new TV shows is that you still aren’t sure how it ended. Record labels need to emulate the boldness with which the leading pay TV networks have sabotaged genre recipes.”

5. Invest in talent and quality.

“The reality TV model, embraced by broadcast networks, is built on the radical view that you don’t need trained actors or high-priced talent. You can take Snooki off the streets of New Jersey and turn her into a celebrity star. HBO and its peers have adopted the opposite approach. HBO spent $18 million to get Martin Scorsese behind the pilot of Boardwalk Empire. When Netflix decided to back House of Cards, they were willing to pay top dollar for Kevin Spacey—Snooki wasn’t good enough. The music industry is still stuck in the old model. They know that the Snooki path to celebrity is the model to follow, because the public doesn’t really care about musicianship and those tired traditional metrics of talent.”

The article certainly provoked debate in the comments section, although much of it seemed to revolve around whether vinyl sounds better than a digital recording. The other big discussion point was who buys music and how important is complexity in compelling that audience to pay?

The first thing to acknowledge is that people appreciate music and TV shows in different ways. A track might be the pick me up that someone turns to now and again, or something to set the mood while they do something else. And even then, there’s no guarantee that that track will be purchased. It could either be enjoyed on the radio, on YouTube or downloaded illegally. In contrast, a TV series is a major commitment of time, an immersive experience that people like to lose themselves in – with no distractions and few compromises in quality. Put simply, it demands more attention than a song or album.

Everyone has a favourite TV drama. Each is likely to be an international phenomenon. Count them: The Sopranos, 24, Lost, The Wire, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, Orange is the New Black and many more. Some, like House of Cards, are guaranteed winners because they are based on our own viewing habits – retailers such as Amazon and Netflix harnessing big data to transform themselves into TV production companies.

No series has raised the bar higher than True Detective in recent years. Obsessing over those first six episodes, pondering them as they took hold of me, demonstrated how far TV drama has come. The scale of ambition. The high concept and depth of emotion. Moments of exhilarating magic like the first appearance of “the monster” Reggie LeDoux or to the one-take shot of Matthew McConaughey’s undercover heist gone wrong. TV hasn’t felt that unsettling and electrifying since Twin Peaks or possibly The X-Files. The formula is easier to spot these days: intricately layered storytelling, deep characterisation, Hollywood-quality direction and production, a sprinkle of A-list talent and a touch of mystery have combined to blur the lines between the box and the cinema. We live in these must-see series on a weekly, sometimes daily basis, freed from the generic and conventional. Open to the elliptical and idiosyncratic. Even the foreign.

Quality at our own convenience is another powerful part of the sales pitch. We need never miss a thing because this is the age of series catch-up and on-demand viewing. Streaming HD-quality video on a giant screen as we put our feet up in the lounge. That’s where we tend to do most of our watching in the UK – 98.5% in fact, according to this Thinkbox survey. Is it any surprise that people are willing to pay for access to a Netflix, Now TV or Lovefilm in addition to their TV licence and/or Sky subscription? In the US, “TV trumps films” on these services, while box office takings are heading south. This serialised entertainment fits into our lives like never before and shrewd investment in talent – from screenwriting to casting – has helped to heighten our appreciation.

So where does this leave the music industry? If executives have learned anything by now, it should be that one size does not fit all. Some people will value unlimited access to a bank of assorted music like Spotify – on any device, anywhere – while others might also appreciate lavishly packaged box sets with liner notes and carefully curated recommendations each month. Across the board, they need to restore respect for the art form and tackle head on this notion of music being a disposable product. The volume of mediocrity and homogenised noise isn't helping the situation.

The way to run a profitable business, one with longevity, is to make something distinct that people want and find very hard to refuse. Using the TV analogy, that could mean raising the quality of releases, both in terms of the music and its reproduction. Neil Young is determined to revolutionise music listening on the go with his Pono Player, although many commentators predict that his efforts will fall on deaf ears. Then there’s the content itself: St Vincent, in a recent interview with The Wire, implied that songwriting could save the industry because it’s an alchemic skill that no auto-tune-like machine can replicate. Not yet anyway. The fact remains: pop music could really do with more craft-oriented stars such as Michael Jackson, Prince, Stevie Wonder, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, the Beatles and Led Zeppelin. Whether their absence is down to poor label management or a lack of musicianship and songwriting ability at grassroots level is too contentious a debate to get into here. In short, we need more standard bearers of depth and skill in the limelight.

In terms of a target customer, it’s a mistake to only focus on adults. We all like some form of music: it is still an affirmation of identity to be able to purchase or cue up your own choice, especially if you’re a young kid growing up. The industry needs to stoke the fires of the youth and appeal to their appetite for the new. In time, they may well come to appreciate the value of music making enough to want to pay for it. It’s a hassle to find torrent sites and click through endless windows of ads. Build the right ecosystem – one that’s easy to use, encourages discovery and is stocked with the music that sounds like it’s fresh from the studio – and it will be very hard to say no if the price point is right for both artist and fan. Getting younger generations to invest time and money in an album will be a lot tougher though.

The listening public is often accused of dumbing down, gravitating towards the lowest common denominator or having dwindling attention spans. I have more faith in human endeavour, that need to make something honest and meaningful that speaks to others. Let’s hope that more stars with substance such as Jessie Ware, James Blake, King Krule, FKA Twigs, Frank Ocean, Banks and Sampha – even divisive figures such as Kanye West and Lana del Rey – will emerge to give us all something to hum along to and pick over for more than a minute.

I miss Made in Chelsea – why "staged reality" still makes great entertainment

So I was chatting to a friend the other day in the pub, prattling on about all manner of minutiae – from heatwave hysteria to house music. Conversation soon turned to the subject of TV and the stupidity of this year's candidates on The Apprentice. Any takers for Neil's DIY estate agency? No, didn't think so.

"How could they pick HIM?" I asked. "These fools are supposed to be some of Britain's brightest young businesspeople." My friend choked on his beer, wiped the froth away and chuckled at my naivety. I had been duped. That's because it makes no sense to have a group of straight-laced and infallible high achievers on a show when the juiciest moments revolve around personality clashes, said moments of stupidity and dressings down in the boardroom. This is not documentary, no matter what the BBC tells you on the iPlayer (where The Apprentice is filed under "factual). The acid test is this: what makes great TV? And candidate selection is like casting, lest me forget the controversy and injustices of past X-Factors that have left a nation in mourning year after year.

I shouldn't be surprised by this thinly veiled deception on screen. The Apprentice has been with us since 2005 and its formula, although one based on competition as much as entertainment, is one that's best described as structured or staged reality – a buzz phrase that pierced the public consciousness in 2011 and heralded a new wave of obsessive viewing after Big Brother. To that category you can add the likes of TOWIE (The Only Way is Essex), I'm a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here, Geordie Shore and, of course, the infamous Made in Chelsea, which documents the trivial dilemmas and entangled sex lives of a bunch of two-faced twenty-something socialites.

The success of these TV shows, both in terms of viewing figures and social media buzz, has revived a long-running debate about the celebrity-obsessed culture of young Britain, with many claiming that these shows are dumbing down – possibly even corrupting – the nation. Not so, says BAFTA. Following TOWIE's YouTube Audience Award in 2011 (voted for by the British public), our hallowed institution of the arts created a new category to acknowledge a TV phenomenon – "Reality and Structured Factual". Speaking after the announcement, BAFTA Television committee chairman Andrew Newman said: "Over the past decade reality and constructed factual programming has captured the public imagination and been hugely influential, while innovating both in content and form." He went on to state that TV production and audiences were changing, and that BAFTA should change with it.

The Young Apprentice triumphed in 2012, followed by a shock win for Made in Chelsea, which prompted this dig from bemused host Graham Norton: "They were insufferable before – what are they going to be like now?" This followed a fuller outburst earlier in the week: "Made in Chelsea really is unwatchable. If you were in a restaurant, you would move tables so, why would you invite them into your home?" he sniped. Lord Sugar was similarly unimpressed. Earlier that night, I'm a Celebrity hosts Ant & Dec insisted that losing out to The Apprentice would be "more respectable".

Insufferable and disreputable they may be, but the cast are certainly going places. Next stop is the US, the land that spawned structured reality prototypes such as Laguna Beach: The Real Orange County and Jersey Shore. There Made in Chelsea is shown on the Style Network, a cunning ploy from TV bosses to capitalise on the 'Kate Middleton' effect apparently (that is, a renewed interest in the young and fashionable upper echelons of British society).

I wanted to take a closer look at TV phenomenon and to ask what keeps 'em coming back. Not everyone can stomach shows like Made in Chelsea, even within the industry. They divide opinion. A producer and a seasoned actor can have completely different takes depending on where their respective priorities lie – viewing figures or artistic merit. But the public is also torn. Here are several brain farts courtesy of Twitter and the Daily Mail comments section:

And one more, a damning verdict… "I have watched one episode of The Only Way Is Essex and it made me really sad; sad for the state of television, sad for the state of the country and sad that my wife was enjoying it too. But what makes me the saddest of all is the fact that (a) people actually WANT to be on programmes like this and (b) that they are seen as having 'aspirational' lifestyles. I suppose you could argue that it's all harmless enough, but who really aspires to be an orange-skinned, cosmetically-altered f***wit who's followed round by a TV crew all day?" – Unknown

There is a conceit at play, so obvious to some that the shows' creators are often not given enough credit. Speaking to the Independent a few years ago, Daran Little, who acted as story producer on the first series of The Only Way is Essex and Made in Chelsea, put it best: "At the heart of this was always a desire to put in the audience's mind: 'Is it real? Are they acting? Is it scripted? Is it not?' and to leave that as an open question for them." He goes on to outline the delicate process of staging. "If there's a boy and a girl in a scene, you'll pull them over individually and you'll say: 'Right, in this scene I want you to ask her what she did last night.' Because I know what she did last night, but he doesn't. Then we start the scene and they just talk it through and if it gets a bit dry, we'll stop and pull them to one side and we'll say: 'How do you feel about him asking you that? Because I think you feel more emotional about it. I think you're pulling something back. Do you think it's fair that he's asking you this?'"

Many characters in these shows provoke pure revulsion, not least Mr Spencer Matthews, resident love rat and baker boy of Chelsea.

A few howlers:

"I wouldn’t sleep with anyone other than my girlfriend ... at the moment."

"I’m so honest with everyone. Maybe it’s a downfall."

"It's kind of hard to respect you when you let me cheat on you.'

"Until the books closed, its open."

As Digital Spy have noted, "The debate really lies in just how 'structured' this 'structured reality television series' really is. Taken at face value, Spencer is a terrible human being and quite possibly the worst man on television. But if Made in Chelsea is as phoney as some critics have claimed, then we're all for Spencer's backstabbing, lies and cheating - it's simply great TV." And that's the point. It's the Marmite effect of the dastardly but lovable rogue and his on-off chums that keeps the majority of the public tuned in. Producers of these types of shows are experts at playing on the line, dreaming up awkward scenarios crowned with irresistible "I can't believe he/she said that" quotes. Creating that world for others to pick at, second guess and gossip about. And Twitter is the instant feedback loop, firing at up to 10,000 comments per minute, that allows them to fine-tune each episode, giving us more of the cringe and hilarity that we love from our favourite characters.

These shows are obviously more popular with the 16-30 age group, who are looking for light relief and something to chat about on a school night. But I am a few years beyond that mark and I still love Made in Chelsea, despite my inclination towards sombre art house films, introspective writers and obscure music. Series six can't start soon enough this autumn. So what's the attraction? Good old-fashioned escapism and silliness, I suppose. To that end, The Call Centre has also been hitting the spot although that's partly down to nostalgia I feel for my halcyon days, when I sold everything from electricity to accidental death insurance.

Whether they come from Chelsea or the Toon, these characters are not aspirational to me … no matter how much fun they have or fame they garner for no apparent reason. But there is a place for everything in our gargantuan schedule: the thought-provoking (Question Time, Dispatches, 24 Hours in A&E); the heart-racing (Luther, Richard II, live sports such as F1); the side-splitting (Alan Carr: Chatty Mann, Twenty Twelve, Britain's Got Talent); and the stomach-rumbling (The Great British Bake Off, Rick Stein's India).

To that list you can certainly add the aforementioned genre – for as long as the creators of Made in Chelsea continue to be inventive with their storylines. The Apprentice? I have time to that. TOWIE? Not so much.

Structured reality proves that the most compelling drama is often real life. Well … with a twist. And if you don't like it, as Bee-bee from Yorkshire says, don't watch.