If your best friend had stolen your childhood dream, would you relive the nightmare 25 years later? That is the fascinating premise for Sandi Tan’s movie Shirkers, which I saw at the ICA last Saturday. It’s another example of the power of narrative-driven documentary – part memoir and part film within a film, all wrapped up in a mystery.

Read MoreStranger than fiction

Rebel without a pause

Attention all beat junkies and collectors of record art. There are lots of screenings of The Man from Mo'Wax happening this weekend across the UK. This is the story of the rise and fall and resurrection of visionary James Lavelle, who emerged in the Nineties to run one of the most daring and infuential record labels in the world.

Read MoreJack Kerouac, painter?

Jack Kerouac, ardent spirit of the Beat Generation, often described his style of writing as “sketching” – an “undisturbed flow from the mind of personal secret idea-words”. There's even a book about it. When he wasn’t “blowing” wild and free like his hero Charlie Parker, Keroauc was using language to gleefully draft his technicolour impressions. So detailed and vibrant were his memories on the page that they became our own.

As early as 1952, he was making the analogy in a letter to fellow writer Allen Ginsberg: “Sketching (Ed White casually mentioned it in 124th Chinese restaurant near Columbia, ‘Why don't you just sketch in the streets like a painter but with words’) which I did . . . everything activates in front of you in myriad profusion, you just have to purify your mind and let it pour the words … slap it all down shameless, willynilly, rapidly until sometimes I got so inspired I lost consciousness I was writing.”

In the same year, disappointed by publisher Harcourt Brace’s choice of cover for his novel The Town & the City, Kerouac designed his own for On the Road, but the book was rejected and lay on the shelf till 1957.

And let’s not forget references like this in the text:

“Marylou was … waiting like a longbodied emaciated Modigliani surrealist woman in a serious room.”

But type in “Jack Kerouac” and “painter” and you get very few Google search results, and no images of the author at work. This is quite surprising as we are talking about one of the most iconic cultural figures in post-war America. And certainly among the most written about.

Some fans will know that in the Fifties he hung out with the New York School – Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning, Larry Rivers, Franz Kline, and Dody Muller (who became his lover). Many are patrons at the 10th St Taverns in the chapter ‘New York Scenes’ in Lonesome Traveller. “They all belong to Kerouac’s poetic universe: that world in which all is fleeting and must be caught instantly, before one moves on to further experiences,” says Sandrina Bandera who is the president of Museo Maga and former director of Brena Museum in Milan.

Apparently, Kerouac’s interest went beyond mere appreciation. He wasn't just a fan, he was a student. “He liked to sit in my studio and watch me paint,” Muller once recalled. “He admired, envied, and was awed by the painters.” So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the fabled poet and author of On the Road was himself a keen artist in the gallery sense.

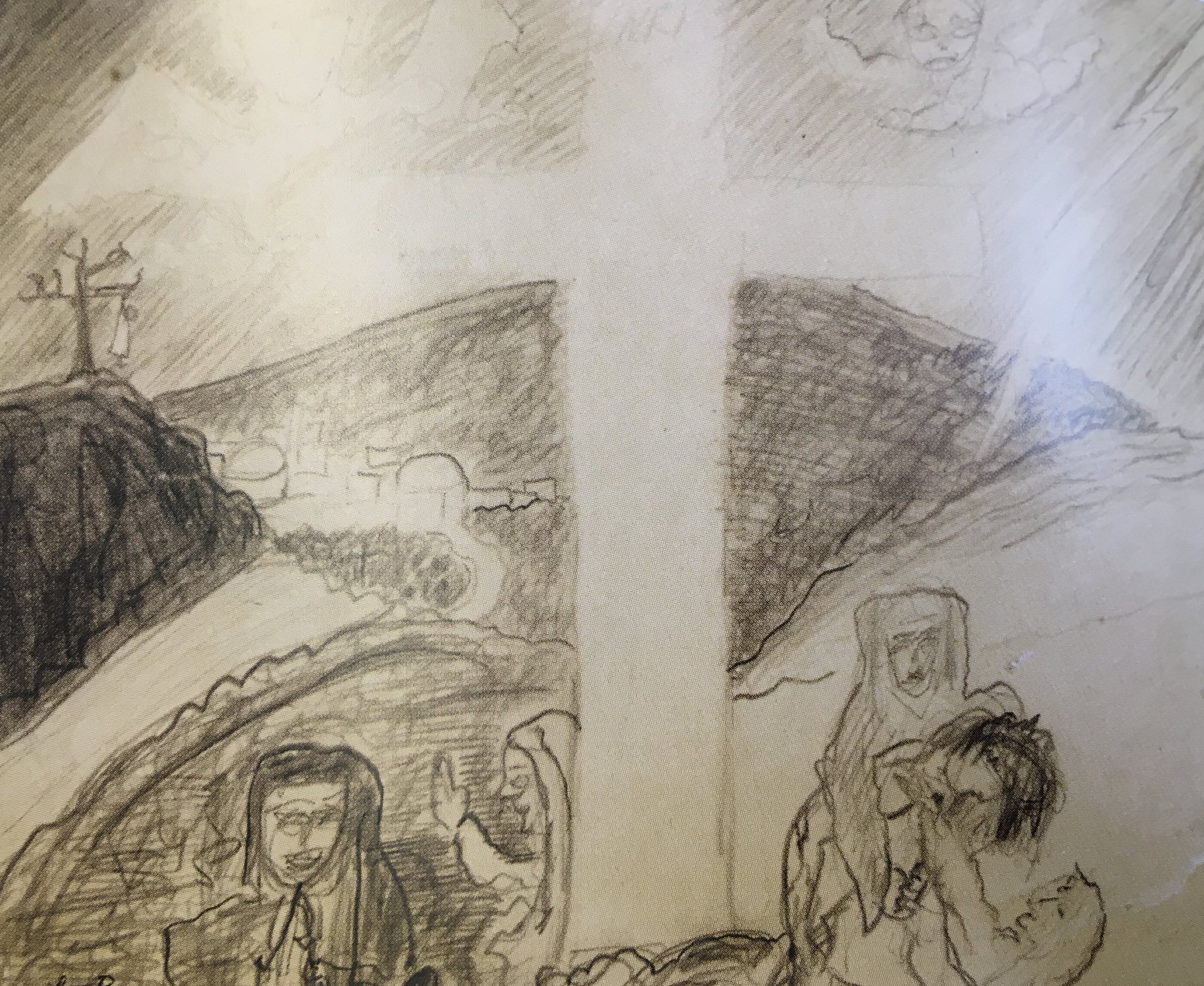

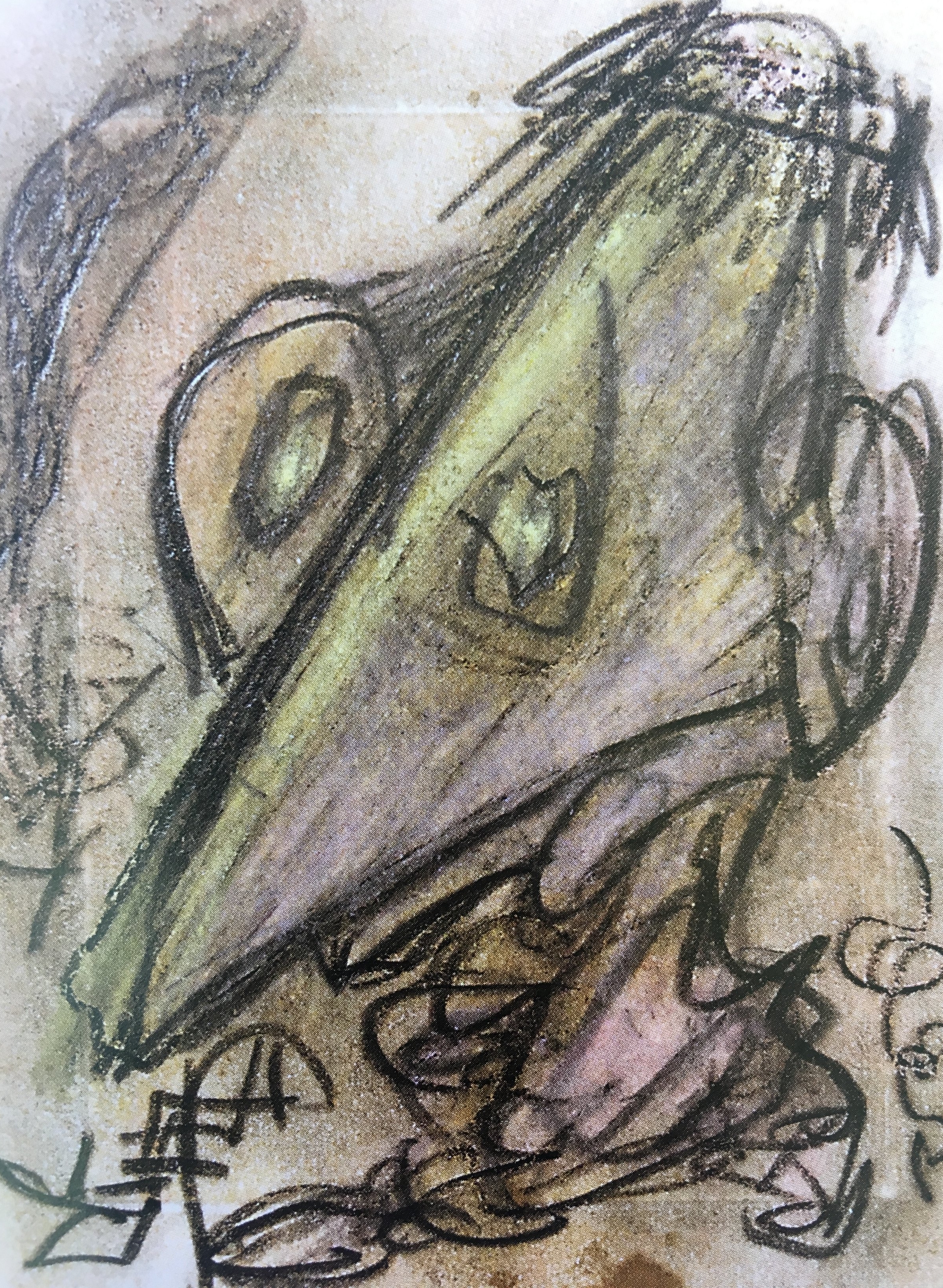

But what would you say if I told you he created stacks of pieces between the late Fifties and early Sixties, from doodled portraits to impressionist scenes and abstract mysteries? Following the successful exhibition of around 100 of his works at Museo Maga – originally given to his brother-in-law John Sampas but later acquired by private collectors – we can all see another side to Kerouac as Skira publishes Kerouac: Beat Painting.

This is only the second print presentation of Kerouac art after Departed Angels: The Lost Paintings, which accompanied the exhibition at New York University in 1994. And the fourth time that more than a handful of his pieces have been shown together, following Beat Culture and the New America: 1950-1965 at the Whitney Museum in 1995 and Beat Generation at KZM and Centre Pompidou between 2016 and 2017.

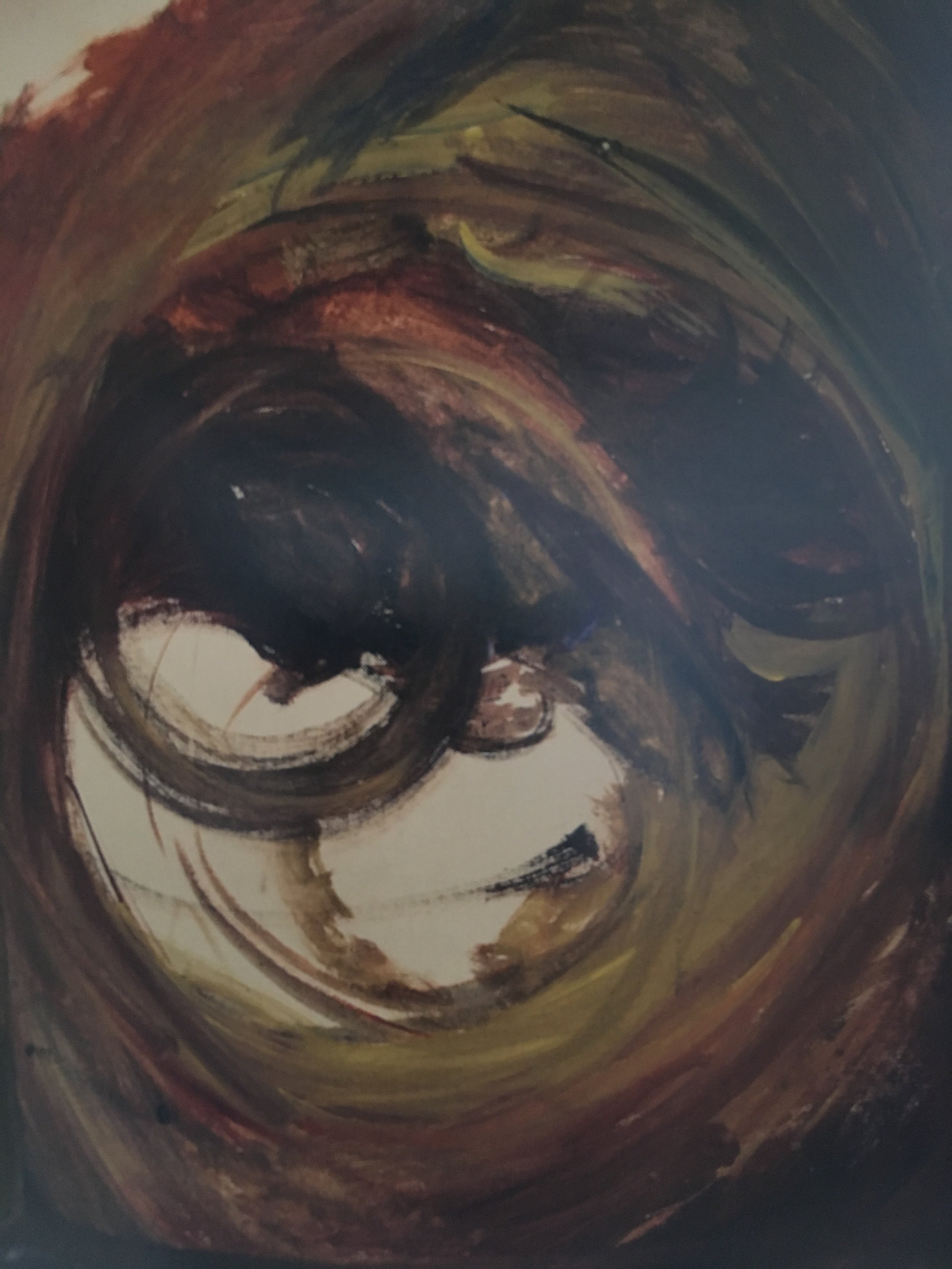

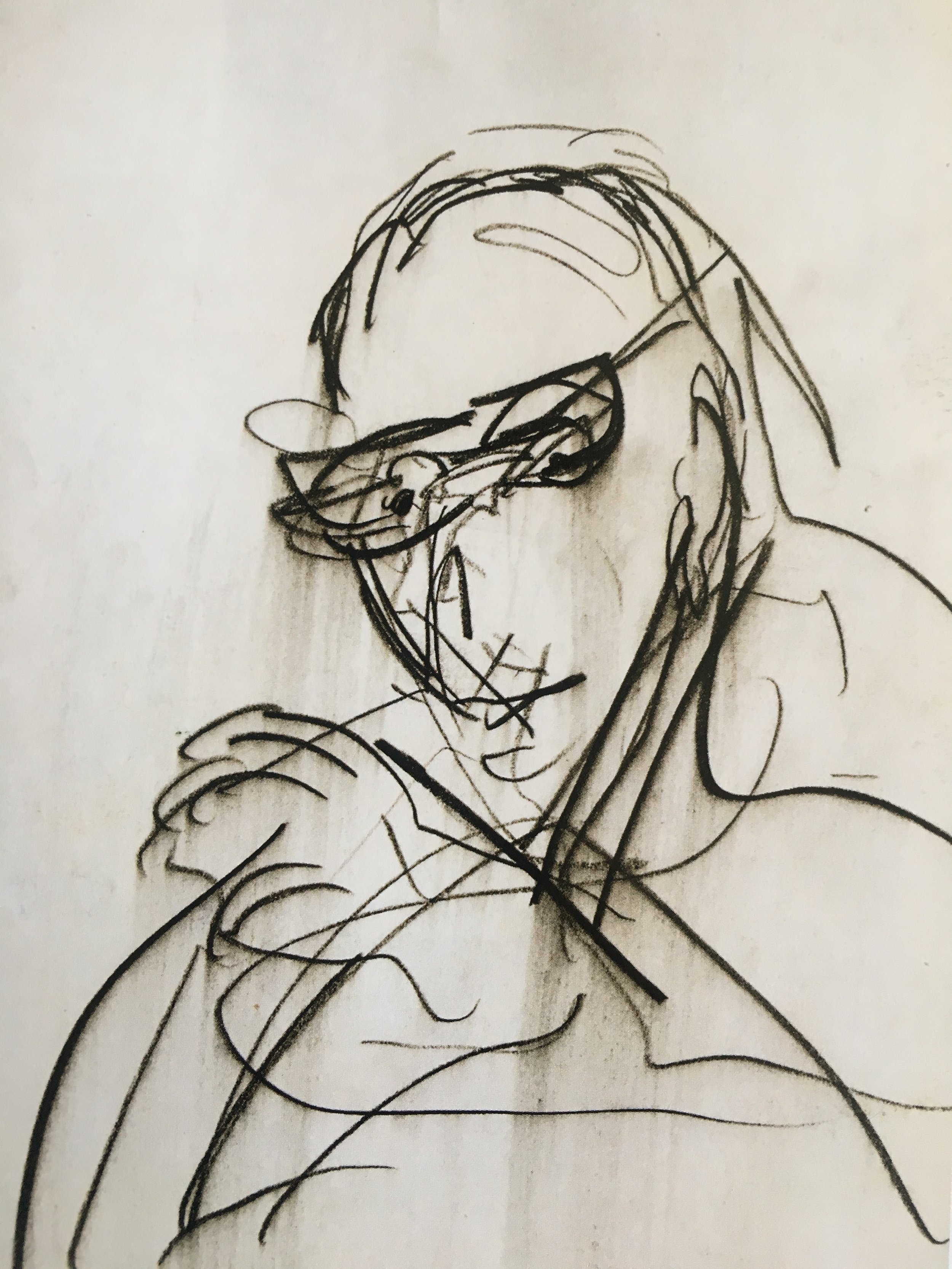

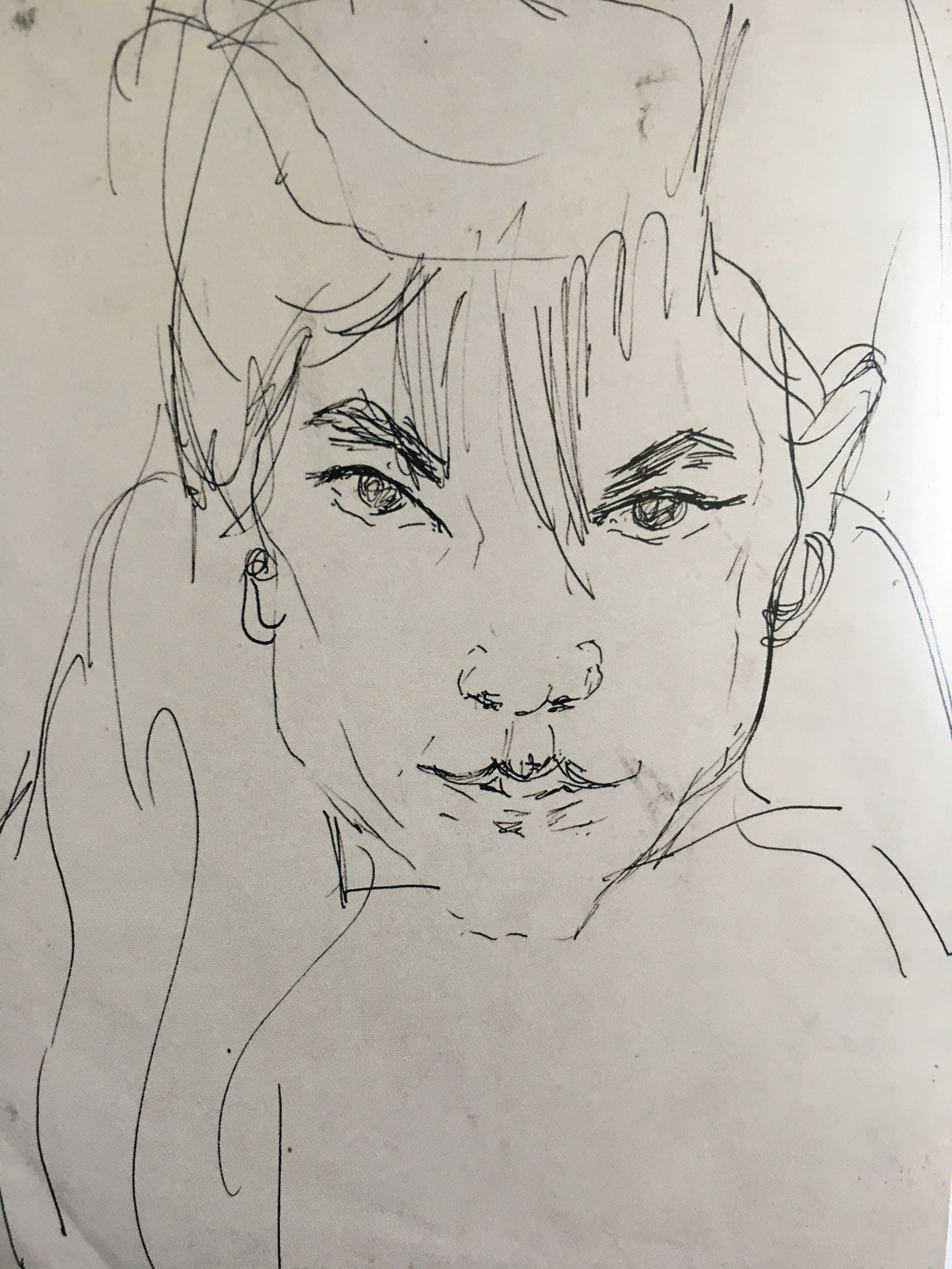

The book is divided into four key sections: A Personal Album (sketched portraits of friends and inspirations), Visions of Jack (sacred imagery, religious iconography), Beat Painting (meditations on the theme) and Abstract Expressionism (gestural, near formless blasts of energy).

The essays that precede each chapter help us to trace his evolution as an artist and lend valuable context to the work.

Here are a few interesting observations.

Kerouac took a trip to Europe in 1957 and visited Provence, the places frequented by Cézanne, and then Paris and the Louvre. “What he absorbed there and aspires to is “exact painting (not imitating) of nature,” says Francesco Tedeschi in the introduction to Abstract Expressionism.

Sandrina Bandera, who co-curates this exhibition, notes that several writers in the Beat constellation – Gregory Corso, Peter Orlovsky, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti – “all accompanied their own writings with drawings, paintings, photographs, music, sounds and rhythm". And that “The Beat writers became acquainted with the counter–culture thanks in part to the English translation of Antonin Artaud’s 1947 biography of Van Gogh.”

Meyer Schapiro taught art history at Columbia University from the 1930s up to 1973. “It was he who aroused the Beats’ interest particularly in Van Gogh and Cézanne, whose works Schapiro considered to be the foundations of modern art,” says Tedeschi.

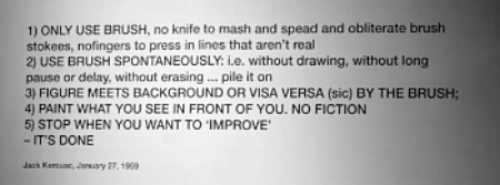

Kerouac had his own rules, which he wrote down on 27 January 1959 –

He struggled to reconcile Catholicism with Buddhism. On the one hand, a devout faith and puritanism instilled by his Franco-American mother. On the other, a spiritual self-less quest for enlightenment in the moment. Or true liberation as he imagined in The Dharma Bums: “I sighed because I didn’t have to think anymore … completely relaxed and at peace with all the ephemeral world of dream and dreamer and the dreaming itself.” The death of his saintly elder brother (aged nine) and the resulting shame compelled Kerouac to write the hagiographic Visions of Gerard and liken himself to Judas in comparison to his Christ-like brother. Gerard was a “spiritual hero, destined to be an angel of Heaven”. That guilt tore him up and you can feel the inner conflict and pathos in much of his confessional writing and painting.

In her essay from the Visions of Jack section, Stefania Benini homes in on particular sacred Christian themes and mystical iconography: “Kerouac conformed to time-honoured genres, such as the Pieta, Ecce Homo (the Holy Face), Golgotha (with the crucified Christ clearly visible) and the Sacred Heart, with distinct reference to sacred imagery in classical painting traditions as well as from popular devotion.” By the end of the Fifties, “dharma was slipping away from his consciousness”. In his time of need, he would once again feel “the presence of angels” but they couldn’t steer him from the booze-soaked path to self-destruction. As Emily Simpson puts it in her brilliant paper, “… instead of serving as a comfort, Kerouac’s relationship with the Church only intensified his suffering.”

In his writing and pursuit of “spontaneous bop prosody”, Kerouac wanted to remove all “literary, grammatical and syntactical inhibition”. He also wanted to tear down the walls between different forms of artistic expression. You can feel the same restless energy and rebellious spirit as you move from front to back of this book. His unwillingness to sit on a particular style for too long, "to break down every distinction between art and life" as critic Harold Rosenberg explained in his book about action painting (The Tradition of the New).

After all, this is the man who was “desirous of everything” and "running from one falling star to another". So he moves from charcoal on paper etchings (The Slouch Hat, 1960) to figurative oil-painted portraits such as Woman (Joan Rawshanks in Blue with Black Hat), the psychic abstractions (The Silly Eye) and "Surrealisme" on the book's cover. Some of his art popped with colour and romanticism, for instance the untitled portrait of a girl in a green dress as she lies in a forest. Others are dark and ominous, like a grey scene from the crucifixion.

I won't attempt to describe the collection in detail, not least because most are untitled and without date, and all are open to interpretation. Instead, here is a selection of favourites.

Ginsberg once said, “If you’re famous, you can get away with anything! William Burroughs spent the last ten years painting [often with a shotgun] and makes a lot more money out of his painting than he does out of his previous writing. If you establish yourself in one field, it’s possible that people then take you seriously in another. Maybe too seriously.”

And he’s right – the last part anyway. If you are Jack Kerouac, people will either expect innate genius or ridicule any attempt to switch medium. There is rarely a middle ground. These works are certainly more than naïve curios from a great author. Although they fall short of being hung masterpieces, they are a fascinating visual diary of a turbulent period in his life, and a resource that you can cross-refer with his writing. The accompanying timeline, which parallels key events in politics and the art world beside major Kerouac milestones, is also very useful.

Kerouac: Beat Painting is published by Skira and available here.

Dispensing culture by the page

Last week I scooted over to cosy bookshop Libreria to celebrate the joy of magazines and one launch in particular. There are lots of pieces on here that gush about the former so let’s focus on the latter. It’s called Drugstore Culture and takes inspiration from Schwab’s Pharmacy on Sunset Boulevard.

No, this isn’t a catalogue of fancy remedies and cures – well, not exactly.

Read MoreGoldfish Bowl – new play, new feel

How accessible is theatre in 2018, particularly to young people in poorer parts of the UK? The West End premium is still a problem and there are never enough offers like this to go around. Meanwhile, the Tate has decided to open all art exhibitions to 16-25s for just £5, a strategy that other major venues should follow.

It’s hard to imagine under-18s in the UK spending what little pocket change they have on a ticket to a new play when they can find what they like online, usually for little or nothing. But this issue goes deeper than cost.

It’s a two-part problem: content and delivery. We need more commissioned voices out there that can directly and very candidly speak of the times we are living in, using (and often subverting) the language and imagery of those times. This is particularly so for those from minority backgrounds. Never underestimate the power of seeing and hearing yourself on stage/screen.

Talawa has been a vital conduit in that regard, and there are occasional breakthroughs like the phenomenally successful Barbershop Chronicles, the vision of Inua Ellams and the product of years of persistent hustle. But these examples stand out because there are so few like them.

Which brings me to Goldfish Bowl, currently running at Battersea Arts Centre for the bargain price of around £10. This is a Paper Birds production starring former Young People’s Laureate Caleb Femi and featuring fellow Sxwks collective member Lex Amor together with the signature visuals of Olivia Twist.

It has been a work in progress for more than two years now, with previous performances happening at the Roundhouse and the Albany. Not many theatre companies would nurture a production with this much patience and love. Here’s a little taste.

I have met Femi a few times while working on this and this for social enterprise Soul Labels. He has been exploring his heritage for several years and pondering what it means to be British through work such as Children of the Narm and this Heathrow installation.

But I didn’t know how much trauma he had experienced between the early years in Nigeria and growing up on a north Peckham estate. Those “dark forces” at play. The car accidents, the fights, the gang violence… Last night he described Goldfish Bowl as his origin story – not how he became a superhero but how he became an English teacher. Is there a difference?

That small theatre was like a portal for the audience. Harnessing very minimal yet evocative set design – a dangling mic, a telephone, a heart monitor made of strip lighting, a cracked mirror backdrop, a hospital gown and a copy of Frankenstein – Femi eased his way into the story through a serious of seemingly off-the-cuff conversations with Amor. It was like two mates ribbing each other in the pub; so playful, in fact, that we were almost blindsided by some of the darker moments to come.

Goldfish Bowl is a whirl, constantly shifting its focal point, tone and topic. The structure was fragmented and the energy off-kilter, which kept you on alert. One moment Femi would be playing schoolyard games and trawling 90’s pop culture with Amor, the next they would be trading bars over a grime beat, or simulating a classroom situation while addressing the audience.

Femi’s transition from conversation to spoken word performance was subtle and moving, particularly when paired with Twist’s animated etchings of the faces and places of his youth. He would turn tender memories of past loves and lost friends into poignant verse, then offer incisive commentary on topics such as the education system and life in Britain as the child of immigrants. This freeform, freestyle approach felt like the only way to tell his nuanced tale – more visceral than film, for intimate than radio. In the open.

In the context of current headlines – the escalation in knife crime, drill music and the demonisation of young black men – Goldfish Bowl resonates even more deeply. But rather than dwell on these issues, which often come to define how others view a whole demographic, this play serves as a reminder that how you respond to certain experiences is more important than the experiences themselves in determining who you become.

Femi was shot aged just 17, something he has described as “a random altercation" and "being in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong person". Speaking to the Independent, he reframed the discussion on gang violence: “You have a group of friends – they’re just friends, your friends. You stick with them. And the more you stick with them, the more you’re associated with your friends. You grow up not really knowing you’re ‘a gang’ – not in the way it’s usually portrayed. If someone troubles your friend, if someone stabs your friend, you’re going to get involved. It happens like that. And before you know it, you’re swept away.”

That day was his wake-up call. As he sits in the hospital bed holding Frankenstein in both hands, like a prayer book offering salvation, he asks, “What is a poem?” In that moment, we understand the power of literature as a means of self-realisation, and the potential of the writer as not only a mythologist but a maker of meaning.

You may not have been born to Nigeria, called Peckham your “endz”, smelt so much of home in a head of hair, made your own entertainment on a council estate, lost “fam” or stared death in the face. But you will recognise what it feels like to stumble, to find your place and maybe, just maybe, to have a dream.

Goldfish Bowl takes you there, as great art should. It’s universal, like a heart that beats for life. And definatly so.

Goldfish Bowl is running at Battersea Arts Centre until 16 June.