Boris v Dave. Eton chums go head to head. It's Tory civil war. Yawn. Over the past few months, it's been frustrating to see the media so obsessed with personalities rather than the actual facts. How is the public supposed to make an informed decision on the EU debate? Forecasts are not facts and neither are estimates. You would think an MP knew the difference, well-educated lot that they are. As one Newsnight audience member quipped, 'Why do the facts change depending on who's giving them?"

Read MoreIn, out, shake it all about

The harsh reality of hidden homelessness

In a recent article on FastCo Create, Andrew Jarecki, who won a Emmy for documentary series The Jinx, presented his new journal app KnowMe. In the interview he argues that people have “a basic human need to tell their story.” He goes on stress that this is particularly true of everyday folk and not just writers or filmmakers. I’ve often said that real life is the most compelling drama and the runaway success of series such as Serial, a podcast no less, confirms that. Now imagine if that story is a deeply personal one that puts a human face on a very controversial, topical issue. That’s exactly what Daisy-May Hudson did when she picked up a camera and started to film her younger sister and mother after hearing that they would have to leave their rented home.

In Daisy’s words, the act of documenting became her coping mechanism. A means of wrestling back control in a frustrating and often hopeless situation. She was in the whirl of her final year studying drama and english at Manchester University when she heard the news and rushed back to be with her family. Their home for 13 years was suddenly put up for sale by owners Tesco and the family were forced to declare themselves homeless because they couldn't afford alternative local accommodation. So began a lengthy period of correspondence with the council in Epping while they moved the Hudsons from hostel to halfway house, often with questionable consideration of suitability in terms of location and condition.

Daisy filmed more than 250 hours of footage, barely featuring herself and instead choosing to focus on her lead characters – one devoted yet ashamed, the other confused and fragile. Daisy’s sister Bronte actually chose to hide the truth from her friends at school; she is an emotional yo-yo on screen, as you would expect being a teenager. But her mischievous and girly moments – from beaming at the thought of a 99% cocoa chocolate bar to singing Beyonce (badly) in the bath – do provide much needed levity.

The resulting documentary, Half Way, which I saw the other night, does a fantastic job of exploring the taboo nature of homelessness and confronting our attitudes to this problem. Credit must go to the editor Vera Simmonds for her judicious cuts and deft pacing while James Smith’s music heightens the mood when needed, without descending into melodrama. At times, it’s an uncomfortable watch. For instance, not much happens … and that’s the problem. The family are stuck in limbo, admittedly not on the streets but undeniably constrained, sharing a kitchen and bathroom with strangers for a year, living out of boxes. We see them struggling to put on a brave face, trying to go easy on one another. You feel the moments of despair with the family, not least when their legitimate objections are misconstrued as the family making themselves “intentionally homeless”. And they aren’t the only ones who stand accused.

For the Hudsons, the experience has certainly left its mark, as Daisy explained to Huck magazine: “I only cried once in the whole year we were in the hostel. I felt like if I showed I was upset, my mum would break. In some ways, our ending was a happy one. When we finally got our home, my mum had to go through a process of de-institutionalisation, re-learning how to make somewhere feel like a home, and not to leave little piles of things in boxes everywhere. Like my mum says, ‘We’re still getting through it.”’

The housing crisis is never far from the front pages or the evening news but the problem is more nuanced than many of us appreciate. That scruffy man on the street begging for a few pennies is only one manifestation. Gentrification, often signified by the arrival of that plush new café in a traditionally working class area, is too easy a target for pointing fingers.

In the Q & A after the screening at 71a London, Daisy, who has become a de facto spokesperson for ‘hidden homelessness’, suggested a raft of solutions – from rent caps to a ban on right to buy and foreign buyers gobbling up properties and leaving them vacant. This is fast becoming the defining issue of modern times in Britain: the right to a safe, clean home and how to facilitate peaceful co-existence in cities amid an impending class war.

Last year Shelter reported that around 100,000 children were going to be homeless at Christmas. More than 1.8 million households are waiting for social housing in England, an increase of 81% since 1997. UK house prices are rising three times faster than average wages according to the Office of National Statistics. If the Government could determine what is affordable based on a family’s income rather than the market rate, and commit units to the rental sector, perhaps we might see some progress. As it is, they are building less than half the number of homes they should be. Planning permission is not the issue.

The Housing Bill, if passed, will make matters even worse, arguably heralding the end of council housing (a “historic moment” but not in the sense that MP Brandon Lewis intended). The Government proposes to replace the stability and sense of community offered by permanent council tenancies with temporary arrangements, reviewed every three to five years. Secondly, households earning more than £30,000 each year (£40,000 in London) will be hit with a pay to stay tax on the difference between their social rent and the market rate. That’s ample encouragement to work less.

There's more. Councils will be forced to sell their “high value” homes as soon as they become vacant but, as Shelter’s John Bibby notes, there is no guarantee in the bill that replacement units will be built. As for starter homes, which Living Wage earner in Generation Buy will be able to afford a £450,000 home (£250,000 outside London) even with a first-time buyer discount of 20%? If you oppose the bill, there is a march taking place on Saturday 30 January from midday at the Imperial War Museum.

Daisy, who now works as a filmmaker producer at Vice and was recently named a BAFTA Breakthrough Brit, hopes to show the documentary to as many people as possible, especially politicians in the House of Commons. She can't understand why people aren’t up in arms about this issue – defeatism perhaps – and urges everyone to hound their local MP and take to the streets. Did I mention that there is a march happening?

Half Way is her first feature-length documentary and it’s a great achievement for someone so young. There is a spirit of defiance and solidarity running through every frame. It’s an honest reflection of the times we live in and could kickstart a revolution if Daisy has anything to do with it.

#SaveIdeasTap – poor funding is killing creativity in the UK

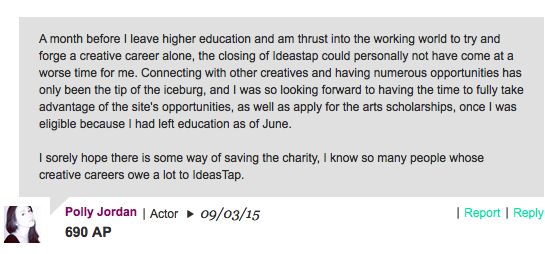

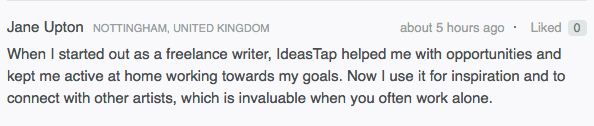

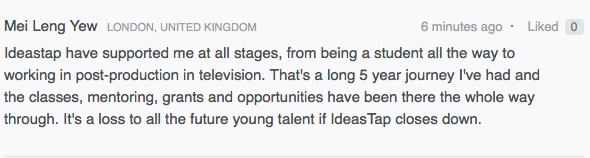

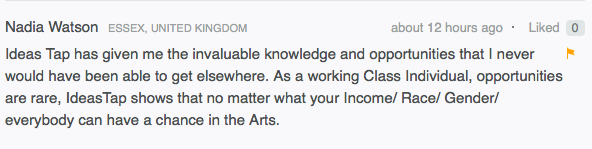

By now many of you will have heard that non-profit arts organisation Ideastap will close its doors on 2 June due to lack of funding. Today there has been a steady outpouring of sadness and impending grief on Twitter, Facebook and their own website.

The news has come as a big shock for two reasons. Firstly, Ideastap has long been a reassuring and encouraging presence in the increasingly uncertain and vertiginous world of the arts. The organisation has been providing cross-disciplinary inspiration and support to emerging artists and creative industry hopefuls all around the UK, not just London, for the past six years. Membership stands at just under 200,000 people – anyone from actors, writers and photographers to puppeteers and aerialists.

Secondly, they've been prolific: running more than 8,000 Spa training sessions; producing almost 4,000 Ideasmag articles, blending answers and advice from established names such as Danny Boyle and Rankin with tips and tricks from alumni still making their way to the top (or "our go-to guide for not fucking things up whenever we have to do something for the first time" as The Human Zoo's artistic director Florence O'Mahoney put it); and providing more than £2.3 million of funding through open briefs, competitions and scholarships in partnership with the likes of Sky and Magnum Photography. Not forgetting a very useful jobs board stacked with full-time opportunities and more unusual paid internships.

In short, young people – and a few more mature types like myself – have been encouraged to develop new skills, get their own projects off the ground, learn on the job and become more business savvy. Ideastap makes you feel like you're not alone. Like the next step isn't so far off. And you don't need to be rich or pally with so and so to progress.

So how can something so cherished and beneficial cease to exist? Chairman Peter De Haan, who founded Ideastap to broaden young people's options beyond costly higher education in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, wrote this yesterday – "Despite our success, to-date IdeasTap has been primarily funded by my charitable trust. Our efforts to secure government or corporate support have failed – and my charitable trust, which was set up in 1999 to improve the quality of life for people and communities in the UK, will soon run out of money. The result, regrettably, is that IdeasTap will close three months from now."

Putting aside sentimentalism and the fact that the arts hold value far beyond revenue – and ignoring the millions all too quickly dedicated to bail out unscrupulous bankers – let's look at the business case. After all, only three letters matter in the modern world – ROI. Or return on investment.

- The UK creative industries generated £71.4 billion gross added value in 2012 – a 9.4% increase that surpasses the growth of any other UK industry sector according to the Creative Industries Council (CIC).

- For every £1 of output of the arts and culture in the UK, an additional £1.28 of output is generated in the wider economy, according to this Arts Council report from 2013. In addition, "The UK’s arts and culture are a very strong draw for international visitors, attracting at least £856 million of tourist spending."

Gross value added (GVA) for 2012-13 increased by 9.9% – more than three times that of the UK economy as a whole, and higher than any other industry (DCMS). GVA of the creative industries was £76.9 billion in 2013 and accounted for 5.0% of the UK Economy. For the fourth year running, the Creative Industries proportion of total UK GVA was higher than the year before, and is now at a record high.

The creative industries accounted for 1.71 million jobs in 2013, 5.6% of total UK jobs; and a 1.4 per cent increase on 2012. (There is a useful list of those industries here together with a breakdown of percentage increases per discipline.)

In a recent press release the government boasted that the creative industries contribute £8.8 million per hour, or £146,000 every single minute, to the national economy. They continue: "As well as entertaining us, the creative industries drive growth, investment and tourism, which is why supporting the sector is a key part of the Government’s long-term economic plan."

If that is the case then what are they going to do about closure one of the primary incubators for this growth? Obviously it would be wrong to wholly attribute success to Ideastap but a cross-disciplinary organisation and flourishing community of this size must have played its part and justified its existence.

If we are going to put the boot into the coalition then let's call in the reinforcements. In their policy review (Young People and the Arts) Labour accused the government of "devaluing creative education" by:

Cutting Arts Council funding by more than 35% since 2010

Imposing the biggest funding reductions in the public sector on local councils, and in an unfair manner. Between 2010-11 and 2015-16, the 10 most deprived areas will have had their spending power cut by 10 times the amount of the 10 least deprived areas, threatening smaller community arts organisations.

Reducing the number of arts teacher training places by 35% in 2012, resulting in fewer specialist arts teachers and fewer hours taught.

Removing film from the national curriculum and cut back on the content of arts subjects.

Abolishing Creative Partnerships, jeopardising benefits to pupils’ confidence, communication skills and motivation, and benefits to the economy of around £4 billion.

Raising tuition fees and axing AimHigher, making it harder for people from all backgrounds to study at university including the creative arts.

Abolishing the Future Jobs Fund which gave work to unemployed young people, including in the creative industries.

Downgrading the apprenticeship programme, leading to a lack of good quality apprenticeship schemes, including within the arts and creative industries.

Unfortunately, Labour has not pledged to reverse any cuts, according to this article. So what next? Count down the clock, say goodbye and move on? Hardly.

The arts community is a spirited bunch and already there are glimmers of hope. A #SaveIdeastap campaign appeared on Facebook late yesterday evening. A petition was raised for the attention of Sajid Javid, Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport – and we know what can happen with these public power plays. There are discussions in progress regarding a rescue plan. Many members and admirers have volunteered to pay a monthly membership fee, a sensible suggestion although some question whether it goes against the principle of Ideastap – a level playing field. Ultimately, the organisation needs a new sustainable model of funding, comprising public funding, corporate sponsorship, a reasonable membership fee and possibly native advertising.

This organisation has been a mighty force for good – instilling pride, developing careers and enriching lives both directly and indirectly. On a personal note, it has helped me immensely in the transition from full-time to self-employed freelancer, and from words to radio and film. Our team is very proud of the podcast series we produced for Ideastap and I sincerely hope we'll work together again. For now, please get behind the #SaveIdeastap campaign. Sign the petition, follow on social networks, download the supporters' pack and spread the word. Artist Paula Varjack is even going to make a short film using public submissions. Simply send a clip of yourself in support, starting with the words "Ideastap is". See the Facebook page for more information.

Let’s fight for what’s right and true.

How one Dalit woman is fighting the caste system in India and winning

Thulasi is a Dalit, a girl from the lowest rung of the antiquated caste system in India. If you’re not familiar with the dangers of being an “untouchable”, this piece by Dalit artist and filmmaker Thenmozhi Soundararajan paints an accurate and bleak picture. “Your family’s caste determines the whole of your life – your job, your level of spiritual purity and your social standing,” she explains. “We live in a caste apartheid with separate villages, places of worship, and even schools. It is a lethal system where, according to India’s National Crime Records Bureau, four Dalit women are raped, two Dalits are murdered, and two Dalit homes are torched every day.” (Sadly, the incidence of sexual abuse among women in India stretches much further.)

Unwilling to follow a set path laid out by her country or society, 24-year-old Thulasi sees herself as a free bird fleeing from marital subservience, the “jail life” as she calls it. Boxing, a passion for more than 10 years, is her ticket to brighter days. She is in a race against time to win selection for the national games and secure a well-paid job through a national program for athletes, before she reaches her 25th birthday. The training is gruelling, an injury threatens to knock her off course and those in charge at her local boxing club seem less than supportive. Something is amiss.

Apparently, “talent is all you need to succeed” at the club, according to the head official at the Tamil Nadu State Amateur Boxing Association. And Thulasi has it in abundance: we learn that she has already defeated five-time world champion Mary Kom. However as the story unfolds we realise that these women must be willing to give a little more than that behind closed doors.

Away from the ring, Thulasi is living hand to mouth with a surrogate family, adrift from her own. “I walked out of my house because I refused to get my religion changed along with other family members,” she later explained to The Hindu. “My parents were unhappy about my decision and I had to leave. There were times when I would get back home late and there would be lechers making a pass at me. I would beat them up. No one should ever question the strength of a woman, boxer or otherwise.”

When this defiance threatens to deny her a fresh start and alienate her even more, we are left wondering whether resistance is futile for an impoverished woman living in a patriarchal state of India. But Thulasi is an indomitable spirit – taking on a male-dominated society in a male-dominated sport – and you can’t help but have faith in her to find a way through. The signs are encouraging: now a trainer at a gym called Combat Kinetics, she plans to open her own boxing club one day.

New generations using sport to overcome financial, political and class handicaps have often made excellent subject matter for filmmakers. Sons of Cuba immediately springs to mind. And like all good documentaries, Like Fly, Fly High makes us care about the star – we're rooting for her from the off. First-time directors Beathe Hofseth and Susann Østigaard let the drama of everyday life take hold – employing a fly-on-the-wall style with minimal narration – never once trying to heavy-handedly disparage a character or engineer tension. The struggle for freedom and progress is something that we can all identify with, wherever we come from. Thulasi is a compelling subject, commanding the screen in any number of situations: contemplating life on her bed, debating the subject of marriage with surrogate mother Helenma or throwing lefts and rights in the ring.

Inspired by Miriam Dalsgaard's photo essay about female boxers in India, Hofseth and Østigaard began thinking about making a film as early as 2005 but it wasn’t until they met Thulasi at Nehru stadium in 2010 that they realised they had to make this film. So off they went on a three-year journey to tell her story, during which time they witnessed a troubled girl becoming a confident young woman. Their ability to capture candid moments about corruption and sexual abuse (a huge taboo) is very impressive, but as they explained at a recent event, their star was always determined to change the world by being true to herself…

“In one of the very first interviews we did with Thulasi, she told us that in India most girls sit on the back of their father's, brother's or husband's motorbikes. But one day she was going to drive her very own bike, so that Indian father´s could look at her and realize what their daughters are capable of. She said she wanted to show people that there doesn't have to be a difference between boys and girls. The fact that Thulasi herself wanted to be a role model to others is what eventually made us decide that we wanted to make a documentary about her. Thulasi is a feminist, without even knowing the meaning of that word, she has a message and we felt that her voice deserved to be heard.”

That interview obviously made a huge impression on the directors. Look at the opening and closing moments of the film and you'll see what I mean. Highly recommended and compelling to the core.

'Light Fly, Fly High', winner of the 2013 Oxfam Global Justice Award and the Best Documentary award at the 2014 One World Media Awards, will be shown at selected film festivals throughout the summer. For forthcoming screenings, click here.

Bad news for the media

"Don't believe everything you read." That's the motto of many where the media is concerned. In which case, who can you trust? Last week I snuck into an informative debate on this very subject, the second in a series curated by Fran Plowright and Free Word. Big questions were asked. What is "news"? Do we need to trust the news? And what are the consequences if we don't?

Among the small but vocal crowd were students under 16 from schools in Hackney and Manchester, together with practising journalists, seasoned pros, keen amateurs and enthusiasts. Before us was a panel of established members of the media industry including Piers Bradford (Commissioning Editor of BBC Radio 1), Angela Phillips (a journalist and reader at Goldsmiths, University of London) and Derren Lawford (Commissioning Editor of London Live, The Evening Standard's new TV channel dedicated to the capital and each of its boroughs).

In light of recent national scandals such as phone hacking and Savile, I didn't expect the public to look favourably upon "the press". Regardless of instances where the press has checked itself – the ITV Exposure investigation on Savile, for example – sometimes even within its own organisation. Nonetheless I was shocked by the depth of distrust felt towards the media. There's one statistic in particular that stuck in my mind, plucked from a survey conducted by Transparency International:

"69 per cent of the country think that

the media is corrupt."

All media. That's a broad brush. That figure is up 29 per cent since 2010. In fact, people think that the media industry is more corrupt than politics. Ouch.

The mechanics of trust in the context of the media industry's relationship with the state is a curious one. The positive influence of national prosperity balanced against the negative influence of corruption and impropriety. It's too big to go into here but consider that levels of trust in countries where government either owns or controls the media (UAE, Singapore and China, for example) is often higher than in countries where media is traditionally thought of as “free” (eg Australia and the UK) according to a research by global PR firm Edelman. Does this mean that people in some countries turn a blind eye if they feel upwardly mobile? Are these results nothing more than testament to the power of propaganda? Incidentally, the same firm revealed figures pointing to a rise in public trust of the media in the UK: up 21 per cent since the phone-hacking case and seven per cent since 2013.

But back to the lecture theatre, and another revelation. When the subject of young people was raised it became abundantly clear that the next generation feels demonised and wholly underrepresented in the media. A recent survey by Demos, "the country's leading cross-party think tank", revealed that a staggering 81 per cent of teenagers felt they were negatively represented in the media. "These negative stereotypes are having a detrimental impact on how they engage with the wider world and their employability," we're told.

A good example is this article in the Guardian, written by a young master's graduate who took exception to a student that rebuffed her offer of a job at the cafe she occasionally works at. What did he say? 'No thanks, I'm over-qualified." Cue a rant about "a certain type of student who looks down on such lower-skilled jobs." Her customer's comment seemed rather innocuous, and the writer's tone was largely cautionary, presenting graduates with the harsh reality of low-paid work in trades far away from their passion or vocation – just to make ends meet. But the article did also paint a picture of the young person as lazy, rude and deluded by a sense of entitlement. Predictably, it prompted a vehement response in the comments section. Here's a taste:

Rabiesx15

20 February 2014 5:03pm

"If minimum wage jobs – that not even a person who owns their house outright could live on – are "gold dust", then what is the point? Students now have to take on real-time debt to study … and then to land in Costa? They have a right to their expectations. The problem is this society first bleeds them then kills their expectations off.

Spoldge4514

20 February 2014 6:03pm

"It's time society stopped attacking; different sections of itself - we have big challenges in the years ahead. We should be working together to tackle them. Sweeping generalisations, stereotyping and one-sided arguments help no-one. I'd like to add I agree some young people are like that. The key word is some. The Commons voted the changes to Tuition Fees into law in 2010. You never see good hard-working [young] people represented in a newspaper. A few shots of them drunk or passed out is the perfect way to provoke an emotional response. Higher education is not a party. Anyone who thinks that is just wrong. Some do treat it as a massive party. But that's some. Why stereotype a whole section of society? Is this not a swinging media agenda? Just because the author was sneered at coffee shop doesn't warrant this piece. The Guardian should be asking why there aren't enough graduate jobs? Why is the labour market so broken? Why has society placed these burdens on their young?

ellamarcel

21 February 2014 3:32pm

To those already working as baristas, barmaids and babysitters while studying this article is really patronising 'advice'. With fees increasing to 9k a year, hundreds chasing every internship and significant cuts in the arts there is probably about three disillusioned students left in England who believe they can walk into a job. One of them must have come into your cafe.

Some strong examples of questionable media conduct were discussed at the #OnTrust debate: the portrayal of Shereka Marsh as a Hackney gang girl first and a schoolgirl second; Mark Duggan's portrait, taken at his daughter's funeral but cropped to make him appear more menacing; how the bulk of the media allow a story and its headline to be dominated by negativity instead of spotlighting positive measures to help (eg self-harm and YouthNet's dedicated response).

So where do we go from here? Obviously a major restructuring and recalibration of the media industry is required, one where newspapers, magazines, radio stations and broadcasters are not only broadening the range of voices and opinions in their programming but also being fair and accurate in the stories they choose to share. In many people's eyes, the newspaper industry cannot be trusted to police itself, which is why the farce of the new Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) has further agitated the public.

I do feel though that it's unfair to condemn an entire industry because of a handful of incidents. There are bad apples in every profession, in every city, and we should remember that it was the press that broke some of the biggest public interest stories of the past few years: Snowden/NSA (the Guardian), MPs' expenses (the Daily Telegraph) and phone hacking (the Guardian).

To those young people who feel voiceless and misrepresented, I offer one word of encouragement: technology. Mad Men's Don Draper blows his fair share of hot air but he was right when he said: "If you don't like what people are saying about you, then change the conversation." You have all the tools, the weapons, you need to make that change. From YouTube channels and internet radio stations to live streamed citizen journalism using your mobile phone, there's never been a better time to shift the balance of power and prove what's really newsworthy when it comes to the youth. I'm certainly fired up now and ready to press ahead with my journalism academy project. Eager to hear how the next generation would change the world. This country has bags of talent and we can't let the wicked acts of the few overshadow the promise of others.

I'll leave you with some key thoughts from the night:

"News is anything you hear that you didn't now before. News is something that is sensitive to both audience and platform." Angela Phillips

"Money is missing from the conversation. Excessively negative and exaggerated stories are often used as click bait. The press is motivated by money rather than what's newsworthy or responsible journalism." A girl in the audience.

"Verification is important. Professional journalists are taught to be skeptical. Bloggers often aren't. Everybody is trying to be the first, but you can be too fast. Good journalism takes time." Angela Phillips

It's hard to get our perspective out there. There needs to be a change in journalistic culture. And not just at a local community level, but also around the big international issues. There needs to be a youth voice in there." Fran, a member of the UK Youth Climate Coalition

"Celebrating youth is an absolutely fundamental part of our job at Radio 1." Piers Bradford

"The vast majority of young people are doing amazing things in this country. If the media is going to hold a mirror up to society, and not a cracked one, it needs to get its act together." Martyn Lewis, veteran TV journalist, news anchor and chairman of YouthNet

"We should be skeptical and question the news we read. But I've seen the great courage of and conviction that drives the work that many journalists do. So it's depressing to see the very low regard in which they are held. Don't necessarily trust but certainly value journalism." Jo Glanville, Director, English PEN

"We need to know what's being done in our name. And journalism does that in an organised way, on a daily basis. We need journalism that connects us, connects us to one another. If we don't then we can't be a democracy. Without the underpinning of information circulating around the world, we'd be all the poorer." Angela Phillips

+ one more thing

The BBC has a produced a very interesting TV debate show called Free Speech. The latest one addresses young people's distrust of another major institution – the police. The nation is still seething from the deaths of Jean Charles de Menezes and Mark Duggan; watch as young audience members protest about racial profiling and the abuse of stop and search powers in a country where black people are seven times as likely as white people to be approached by the police. According to the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) that figure is as high as 29 in some areas. Nonetheless 61 per cent of the viewers at home thought it was right for the police to judge us on the way we look. As with the media, conduct is the crucial factor.

![Daisy (left): "[Our society] has a culture of blaming the individual and not the archaic, profit-reaping system that allows things like this to happen. This is evident in the ‘scrounge’ narrative that plays out in the media and in politician’s speec…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/505875d2c4aa5fcea75608a9/1453668319503-XNOE1FHL0C4ZZSGOP0GP/Half-Way-daisy-mae-hudson)