The last time I went to the cinema was more than 18 months ago. On Sunday I settled in for Summer of Soul at Catford Mews. A music doc fan feeling highly expectant though dazed by the baking weather outside. To be hit with this rush of on-stage brilliance – after months without live concerts and gigs – was overwhelming.

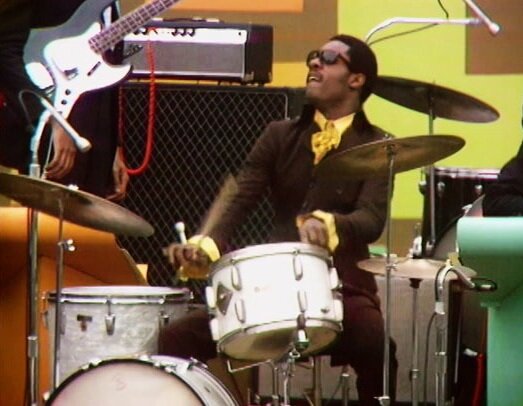

Look, there’s Stevie Wonder in a fitted brown suit and frilly lemon shirt knocking out a thunderous drum solo beneath an umbrella. A new flex. Not a bad way to open. You’ve got velvet-suited David Ruffin, who’s just left The Temptations, reminiscing about ‘My Girl’ with the 50,000-strong crowd.

Exile Hugh Masekela – no stranger to oppression and police brutality – blowing out across a sea of weary brothers and sisters like a clarion call to freedom. Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln just shining with majesty and doing what they do – living “unapologetically black”. The Chambers Brothers biggin’ up Harlem with their infectious rhythm & blues.

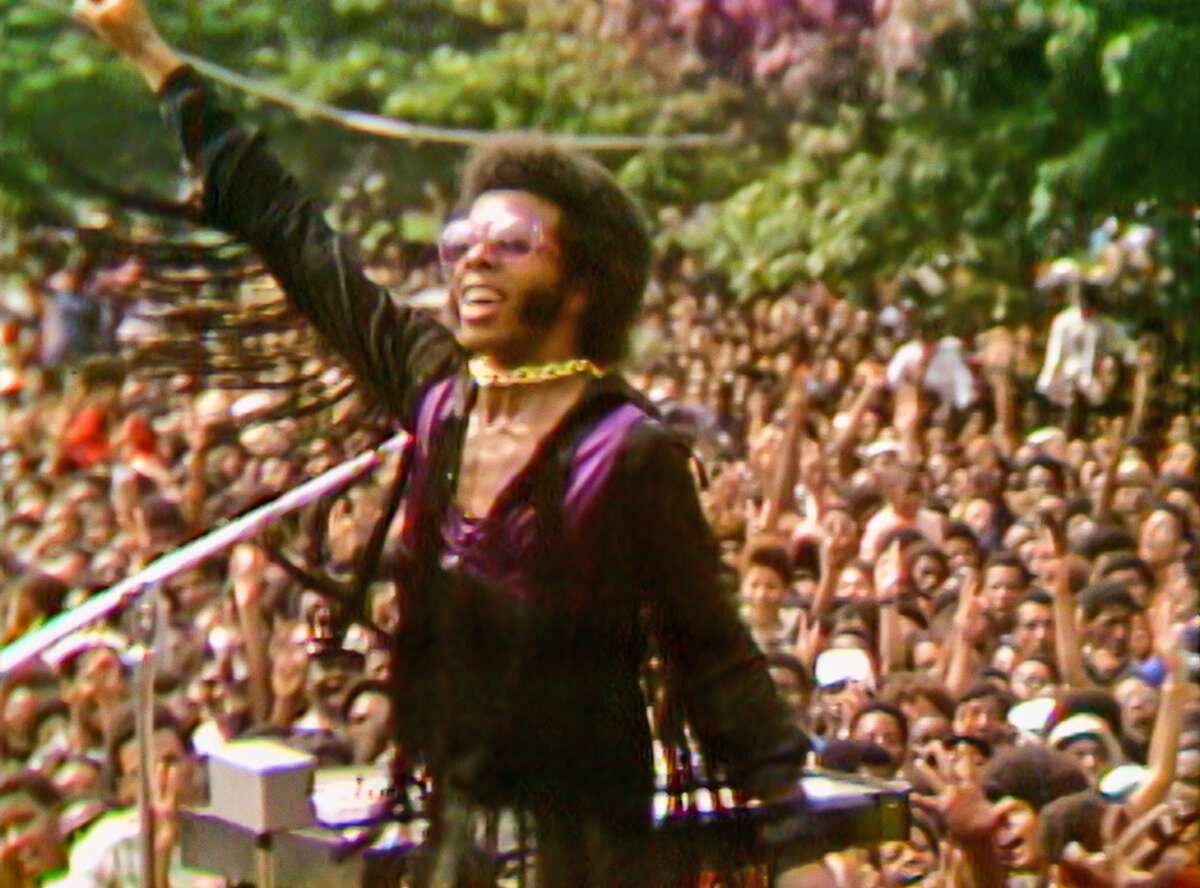

Sly Stone appears on stage as if from another dimension, together with his interracial psychedelic soul family, prompting a stampede to the front of stage that threatens to halt the show. Some of the crowd are bewildered by their otherworldliness – the clothes, the unfamiliar groove, a white man on drums, a woman on trumpet – but by the end of their set, songs such as ‘Everyday People’ and ‘I Want To Take You HIgher’ are doing just that.

There’s The 5th Dimension in their orange-tasselled suits, coming home as they offer a spun-out take on ‘Age of Aquarius’ (from the musical Hair), a ubiquitous hit that had conquered the airwaves that spring. Even the likes of Ray Barretto and Mongo Santamaria are there, throwing down on them congas.

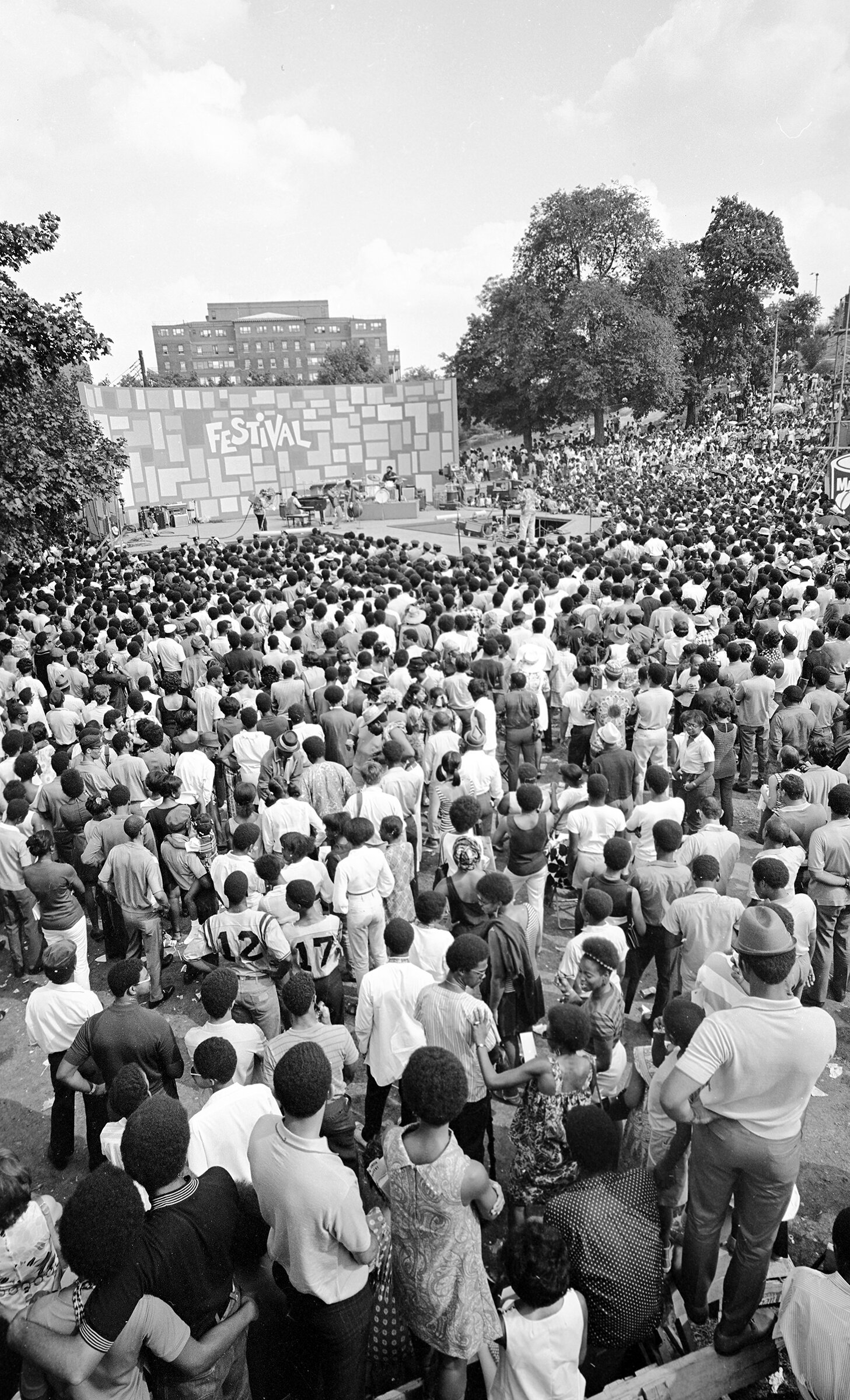

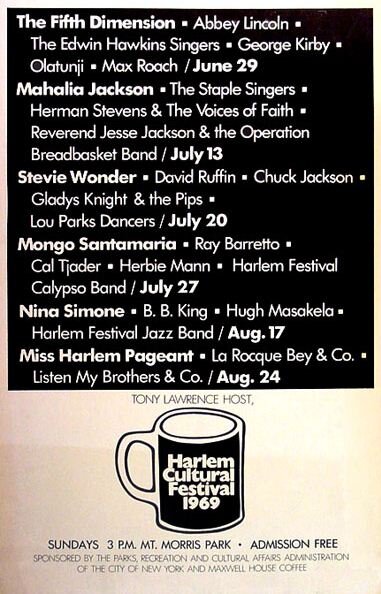

In a fever dream, this could have all happened on the same day but Summer of Soul actually documents Harlem Cultural Festival – a series of free concerts which took place over six weekends in the summer of 1969 at Mount Morris Park. This was the third and biggest edition, a turning point in black consciousness, a liberation.

It’s almost impossible to convey the turmoil of that period, particularly what it felt like to be black and under threat in America, but this time capsule of film sets the scene well through archive footage and crowd reactions. (Wattstax aside, I’ve never seen a concert film that gives so much screen time to faces in a crowd. That’s a huge part of its charm.)

Think about it: the progressive JFK assassinated in 1963, Harlem’s own Malcolm X in 1965, Dr Martin Luther King followed by Bobby Kennedy in 1968, the Vietnam war is raging on, magnifying the trauma of black soldiers…

The Civil Rights Act has been expanded and yet black people are still experiencing discrimination, poverty, hostile environments in desegregated schools. Meanwhile, they’re putting a man on the moon (right in the middle of Stevie’s set, in fact). Amid a chorus of boos, one man sums up the prevailing mood about this jingoistic misallocation of funds: “What’s on the moon? Nothing!”

If Summer of Soul only gave us a string of incredible performances, it would still be a triumph. But we are also witnessing a mass communion of black joy in the face of persistent hardship and tragedies. Hip youth in their dashikis, floral patterns, fly shades and fros looking hopeful as they rub shoulders with churchgoing elders in their Sunday best. Awestruck kids, bop, sing and dream of what could be. Harlem Cultural Festival stoked the pride of each and every one of them. As Rev Al Sharpton says in the film, 1969 was the year that “the negro died and black was born”.

And language is important, as demonstrated by an interview with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, who became the first black female journalist in the New York Times newsroom. She fought her editors to make the switch from “negro” to “black”, to reflect this awakening.

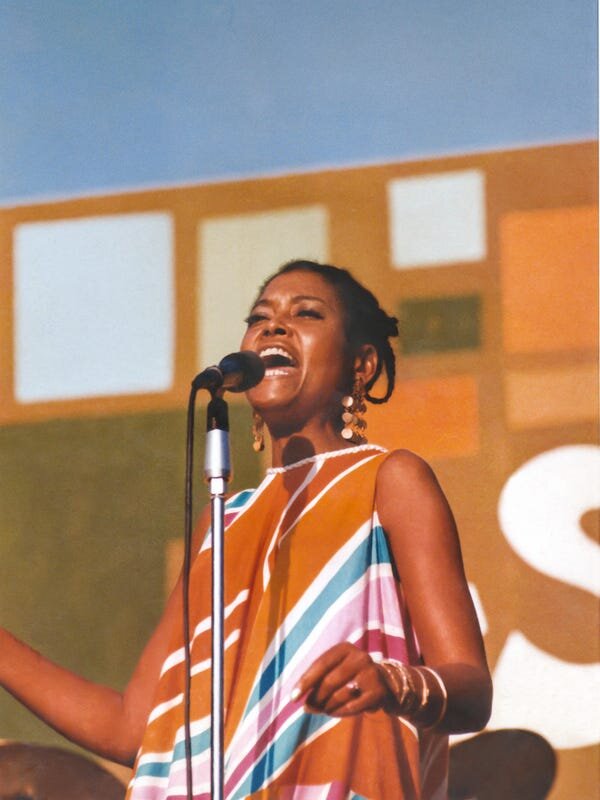

Perhaps Nina Simone’s set best evokes this affirmation. She saunters regally to the piano wearing a crown of braided hair and earrings like antiquities, sitting down and pummelling the keys as she reminds everyone that they are young, gifted and black. The climax to her incendiary set is a recitation of a black nationalist poem by David Nelson. “Are you ready to smash white things, to burn buildings? … Are you ready to build black things? Are you ready to kill, if necessary?” she asks to a chorus of yeahs.

With this new attitude of self-determination and defiance came a more ambitious approach to enterprise and cooperation, according to the Houston Chronicle. “For black folks, the added power and energy of coming together in a place where one could not only see hear and feel blackness on stage but also participate in a marketplace of neighbourhood business owners was its own form of sustainability.”

Two big questions arise. How the hell did this festival happen and why are we only hearing about now? We learn that exuberant, St Kitts-born entertainer and host Tony Lawrence was a key driving force – a vital bridge between the Parks Department, white politicians with national aspirations such as NY mayor John Lindsay and black community organisers including Reverand Jesse Jackson who features in the film. (Lawrence even secured Maxwell House as a corporate sponsor, though they lent a little too heavily on their link to “the dark continent” based on the ad we see.)

You can see the motive of allies such as Lindsay. With riots a real possibility, this might be a good way to quell potential unrest in the city. Sadly not everyone got behind the event, namely the indifferent/discriminant NYPD, so the Black Panthers took care of security. And it’s worth mentioning that, the festival “came together with no significant trouble, no arrests and no record of public inconvenience,” according to Harlem ’69 author Stuart Cosgrove.

Contrast that with its correlative, which would take place a hundred miles south and two weeks later. It promised “three days of peace and music” but, depending on who you talk to, ended up being a crashed party that overwhelmed promoters and authorities. The fact that Woodstock is remembered as a countercultural milestone might have something to do with the widespread availability of the film.

Lawrence subsequently tried to take the festival on a national tour but eventually gave up due to a lack of private funding. He also claimed there were shady goings-on, including an accusation that funds were stolen by his lawyers and business partners, Jerrold Kushnick and Harold Beldock.

Hal Tulchin is a hero in all of this. He shot the footage and was resourceful enough to build the stage facing west so he could film all afternoon without expensive lighting. He tried again and again to turn his footage into a documentary, approaching production companies and TV networks and pitching it as the “Black Woodstock”.

A couple of WNEW-TV one-hour specials aside, Harlem Cultural Festival remained barely a footnote in black history until those 40 hours of footage, immaculately preserved in on two-inch reels despite laying in a basement for more than 50 years, found their way into the hands of producers Robert Fyvolent (who first approached Tulchin in 2007) and David Dinerstein in 2017.

Not even Questlove knew about the festival until approached to direct. Amazing when you consider how deep this man’s crates are, how voracious and encyclopaedic he is about music, movements, lineage. He lived with the footage for five months as it played on loop around his home, eventually curating this film like a DJ set. The first cut was beyond four hours. And we’ve yet to see more than 60% of Tulchin’s footage.

My highlight from Summer of Soul will take some beating though. We see Mahalia Jackson inviting a young Mavis Staples to perform a rendition of Dr King’s favourite song ‘Precious Lord, Take My Hand’ [which he asked accompanying saxophonist Ben Branch to play the day he died]. It’s a passing of the torch. But then Jackson must like what she hears, or the spirit takes hold and she joins. Stood there together sharing the same mic, summoning all they can give, it’s as if right there and then, the magnitude of this glorious moment hits them. They soar and soar. And we join them.

Where’s Hendrix? Surely he should have been on these bills in 1969? Well, he was turned down according to Questlove. Instead, he played a series of unofficial aftershows in Harlem spots with Freddie King. Then came Woodstock and you know the rest.